It’s been a long year since Emad Shahin, 17, was shot and captured by the Israeli military when he snuck under the border fence with several other protesters from Gaza’s Great Return March.

Emad finally returned to his family on October 23—in a body bag. What happened in between is a troubling, tragic mystery.

Who was Emad Shahin?

Emad was the youngest of 9 children. His father made a small but decent salary as a school janitor and he grew up loved, spoiled and smart—particularly in reading and math, says his sister Monira. Mathematical equations intrigued him. But he also was a very stubborn boy, finding it hard to share his belongings. During the summers, he attended a camp organized by Hamas, since his parents are members.

“But the activities were just for fun and to fill up his time during the time off of school,” says Monira, who was older than Emad by 13 years and considered him like a son.

The mystery

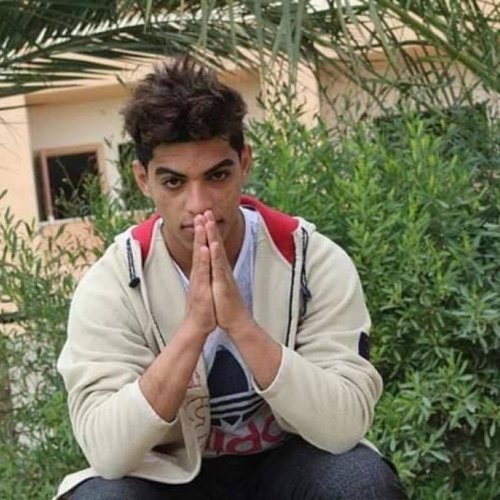

Monira recounts these events: When the Great Return March kicked off March 30, 2018, her entire family participated. However, while she and the others stayed further away, Emad ran close to the border fence, burning tires so the Israeli snipers couldn’t clearly the protesters as they aimed. It wasn’t long before the snipers shot Emad in the foot.

“Emad had a personality of resistance though,” says Monira. “He healed quickly and just two weeks later he was back in the protest using crutches. When photos of him out front despite his injury were widely shared on social media, he felt proud. He saw himself as a symbol of the protest.”

Twenty-one Fridays later, Emad was shot again, in the same foot. Still, he returned to the march. When he was shot a third time, this time in the other foot, surgeons were forced to amputate three of his toes. “Our mother tried to stop him from going back. The entire family told him he had done his duty for his country and should rest now. But said he said he did not fear death, that death is inevitable, and he’d rather die for his country, resisting occupation, than some other way that is pointless.”

Thinking of early death as inevitable in Gaza is the prevailing point of view. But for Emad, it was a particular conviction. His brother Ibrahim, older by just one year, had already died. The two were very close, sharing the same bedroom. When Ibrahim was in his final year of high school (so critical in determining whether a young person can continue on to university and in what he or she can major), Emad stayed up nights to help him study, making the surrounding environment as comfortable and peaceful as possible. When Ibrahim achieved a high score, Emad celebrated for three days like it was his success too. On the fourth day, Ibrahim was killed in a fight with a friend.

Emad was inconsolable, keeping Ibrahim’s bed neatly made and talking to him at night even though he knew he could not hear. “Every time Emad was missing at home, we found him at Ibrahim’s grave, praying for him,” Monira recalls.

Better to die resisting, Emad thought. And thus, his participation in the protests became more even more daring.

One Tuesday, Emad and two friends decided to cross through the fence between Israel and the Gaza Strip, trying to reach a vacant Israeli army barracks almost 300 meters inside the fence. The goal: to challenge their imprisonment, bringing back a “trophy” like soldier’s ammunition belt or a jeep license. They made it, and Emad called his sister on his mobile phone, out of breath, as they prepared to leave.

“He wanted to share his triumphal moment, but I shouted at him, ordering him to get out immediately before he was killed. I was terrified!” Monira shudders. “When he made it home, he said he wished he had burned the building down. But he is not trained for such maneuvers and my mother was in tears, asking him to not do so again.”

The following Saturday, Emad awoke he early, telling his mother only that he was going for a short errand after breakfast. But in actuality, he returned to the empty barracks with his friends, carrying gasoline. They managed to sprinkle some gasoline on the ground and start a small fire, but then fled, says one of the friends, who asked to remain anonymous.

“We ran until we found a mound of sand to hide behind on the other side of the fence, but then noticed Emad was not with us. He ran slower because he was on crutches,” he explained. “We saw him on the ground and called to him, telling him to crawl. But then a military vehicle raced up and a soldier fired at him, shooting him in the right leg. Soon, a helicopter came and took him away.”

Monira says the family contacted the Red Cross and Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights, frantically looking for information on Emad.

The end

Mervat Nahal, an attorney with Al-Mezan, takes over the story. “We learned that Emad was taken to Soroka Medical Center in the Negev. We contacted Physicians for Human Rights, which was told by the hospital that Emad had died, and his body had been handed over to the Israeli army. We demanded his medical records but were denied. The Israeli army also refused to return the body.”

Nahal says Al-Mezan then contacted HaMoked, an Israeli human rights organization, which also tried to obtain Emad’s body. No reply was received. The three NGOs kept trying, however, until a year later, when they received a letter saying the boy’s body had been shipped back to Gaza.

To say that Emad’s family was shocked and devastated is an understatement. “We knew he would be imprisoned, but not murdered,” Monira says. The family had held on to a small hope that Emad was actually alive. After all, where was his body?

When the call came from the International Red Cross, saying Emad had arrived at Al-Shifa Hospital in Gaza city, the family rushed there. According to the Dr. Emad Shihada, the receiving physician, the boy’s body had been stored in liquid nitrogen at an extremely cold temperature for a long time. To perform an autopsy would have required 48 hours in the sun to “thaw” the body, due to the lack of proper equipment. And the family preferred to bury him rather than to wait. Islamic tradition calls for immediate burial after death; the sacred rite already had been delayed too long.

What could be seen without opening Emad’s body, however, was troubling to the family. Signs of stitches stretched for 15 centimeters from the middle of his chest to his stomach. The same scarring pattern could be seen for 13 centimeters radiating out from the area of his heart on both sides of his body. Monira says the family suspects his organs were removed for sale—a practice that had been common in Israel prior to the passage of a 2008 law banning the business. However, Dr. Shihada says it is possible the boy’s body had been opened by physicians in an attempt to stop internal bleeding. External examination showed that Emad had been shot three times in the right leg. If one or more of the bullets severed the femoral artery, causing him to bleed without treatment for more than 15 minutes, that alone could have caused his death.

“Emad was only a boy,” Monira says. “Israel could have treated him after he was abducted. But they did not. They killed him.”

Instead of being scared off from the Great Return March, Monira says her family never misses a Friday.

“Resistance is the only way to liberate our land,” she says. “And now we also go to honor Emad. Now the whole family is ready to die to defeat the occupier.”

Originally published in another form by Middle East Eye.