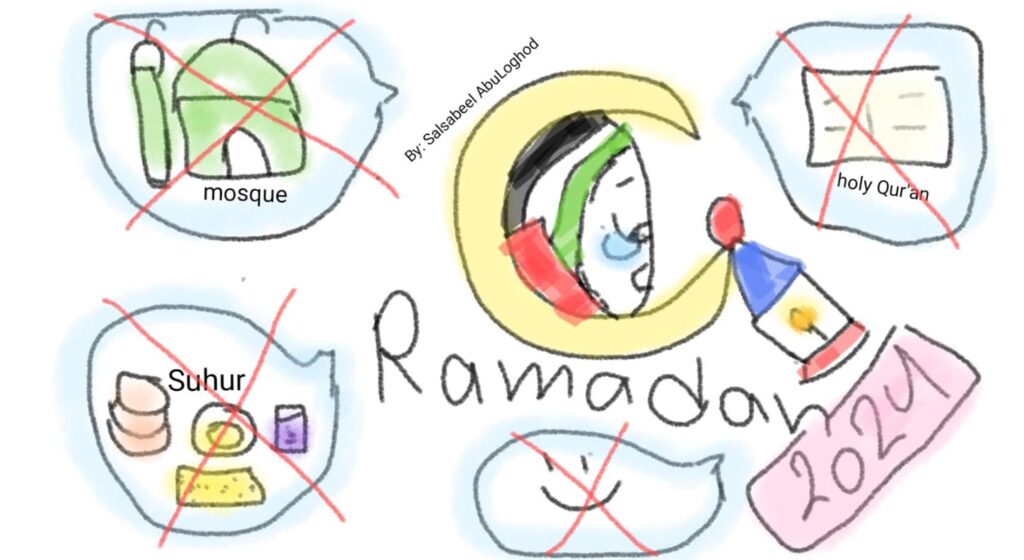

Ramadan has always represented a beautiful occasion for every Muslim in the world. But the Ramadan of 2024 was void of a religious soul and was the most tragic month of the year for Gaza. It was a month of tears and blood.

The familiar voice of the Masaharati, who wakes the people for suhoor in Ramadan, never rang in the early morning as he had always done.

Suhoor itself, the early dawn meal permissible for those fasting — with the array of white cheese, labanna, yellow cheese, eggs, jam, vegetables like tomatoes and cucumbers, halawa tahini, milk, hummus and beans — was also nowhere to be seen or smelled or tasted. This simple meal with a warm cup of tea had given us warmth and happiness. It reminded us of the purpose and meaning of Ramadan.

This war has robbed me of the joy I used to feel from preparing suhoor. This Ramadan, we had only water to start our fast and no food. Sweets, like katayef, once abundant and which infused the nights of Ramadan with long-awaited festivity, were also starkly absent. I have even forgotten what they taste like, for few can afford the high prices charged for desserts nowadays.

The streets of Gaza once burst with the lights and colors of Ramadan. But this year, the streets were without shape or memory of this holy month and I failed to extract one scene that could return the joy of Ramadan to me.

My father told me of a place that once sold famous Ramadan gifts for children, but no one went to buy anything from there this year. The money had to be saved for buying food if we found it. A day later, my father told me the place had closed. Was this really Ramadan or just another terrible month which we hoped to survive?

An Iftar without tastes

The sadness did not end during suhoor, nor did it leave our streets. Instead it continued into iftar, the meal eaten after sunset to break the fast. A lot of people were only able to drink water while others accepted what meager food was available like khobiza, a brothy soup made from a wild green plant.

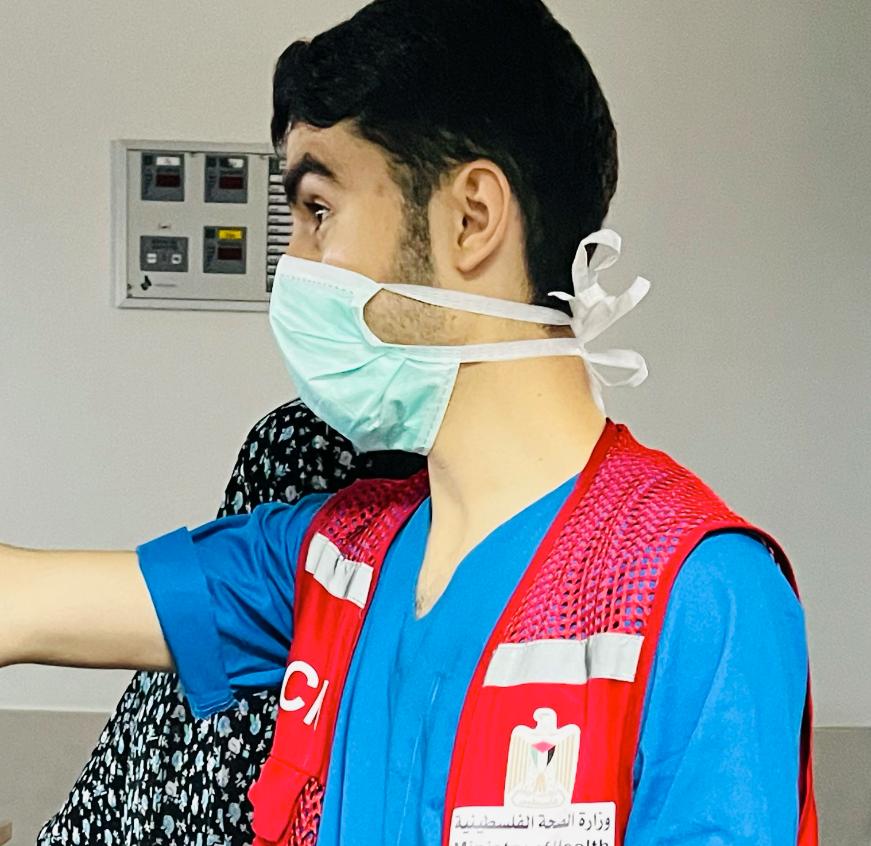

Everything turned against us. The rain that watered the plants and nourished our khobiza stopped during Ramadan. The banks too were closed because the Israelis bombed them in the center and the north of Gaza, leaving us to borrow from others and pay 10% commissions. To make matters worse, we had to pay exorbitant prices for food when we did find the money.

The taste of iftar with traditional sweet juice, meats, rice, salads, and other different flavors lived only in our imagination. Long gone was the intimate atmosphere of cooking with my mother and family along with the aroma of spices and fresh bread. We even resisted baking bread because the tanks used for cooking (there was no gas for ovens left in Gaza) sent acrid fumes of smoke that choked us.

Our bodies lost the power the suhoor gave them, and our souls wanted to scream, “Stop the war! We want to feel the moments of Ramadan without the sounds of bombs.”

Religious moments with subdued hearts

Even the precious religious moments of Ramadan, such as reading the holy Qur’an and praying Taraweeh, were without soul and focus. Our minds and hearts had grown exhausted. Almost every mosque has been destroyed and we were deprived of the Athan, the call to prayer, that signaled the end of our fast. Even praying Taraweeh at the mosque was denied us. There were no Ramadan moments in Gaza.

For one fleeting moment during Ramadan, the beaming faces of children on the street near my home pierced the sadness. Just after the iftar, following the Alashaa prayer — in the evening — a man came with a tank and hit it with a stick. He repeated the words of the Masaharati, yelling, “Wake up for the suhoor” and began singing the traditional songs of Ramadan.

The children gathered around him, laughing and giggling at his call to wake up when they were already well awake. This made me happy for a little while. Unfortunately, the happiness of the children did not last beyond the first three days of Ramadan when the visits of this comical Mesaharati suddenly stopped.

Meanwhile, the whole world watched the crimes against the Palestinians in Gaza, especially against children and women, without an end in sight.

An Eid Al-Fitr deprived of joy

Eid Al-Fitr, which follows Ramadan, was equally morose. The happiness of taking the Eidiya, money that relatives give to women and children, was wiped from our faces. There was no Eidiya this year and I wonder what else this war will rob us of.

I miss walking on the streets at night with my family and seeing the black skies of Gaza light up with the zina, decorations, of Ramadan. The streets are destroyed now without the echoes of laughter from children and the nectar smell of sweets. The sadness envelops every street and the bombs still knock at our doors and kill everything that moves, be they animals or humans.

The words “I miss” were on the lips of every Palestinian this Ramadan. And even harder to bear was the sorrow of missing lost family members. I heard the pain of losing not just a home but entire families when I heard “I miss him (or her or them).”

My friends who live in Gaza, in the same city and country as me, are also so far for me to reach and I ache for them. I can’t connect with them because we have no internet and I don’t know if they are alive or not. Their absence and disappearance from my life made Ramadan the loneliest month.

The war continues to fill its belly with our bodies well past Ramadan and Eid. The suffering continues but no one is moving to stop it. The people in Gaza are malnourished and starving and we are but bones walking on the streets. Palestinians will always remember this as a time when many turned their back on us. But we take comfort that Allah will protect us.

Thanks to fellow WANN writer Asma Abuamra, who served as an electronic intermediary with Salsabeel’s mentor to help overcome internet connectivity issues in the north.