I was cleaning out my dresser drawer when I found some old photos of my mother. I took the photos to the living room, where she her face was burrowed in a book, glasses perched on the tip of her nose. I walked slowly toward her. I remember the smell of her coffee. The shouts of the boys playing soccer in the street. I was 17 years old and I decided it was time to know more about the woman in the photos. The woman who has lived through so many wars. "Mom," I asked. "Will you tell me about your life?"

Eight years of separation

My mother was six when the 1967 war erupted. Her father, my grandfather, was working in Saudi Arabia at the time. He was a carpenter and could not get home to his family. During the

war, my mother's grandfather drilled a two-meter-deep hole, and this was where they hid most of the day, like so many other Gazans. My mother remembers the noise most of all. Each time they heard the piercing sound of the warplanes above, they all ducked down, pressing their palms over their ears.

One day, there was a thumping on the door. My mother recalls scurrying into her mother's lap, crying as Israeli soldiers stormed the house in their green military uniforms, their guns over their shoulders. They searched every corner. They found nothing. They left.

After the war, the Gaza Strip fell under total Israeli occupation. No Palestinian was allowed into Gaza without an Israeli passport—not even those who called Gaza their home. That meant my grandfather was stuck in Saudi Arabia; he could not return home.

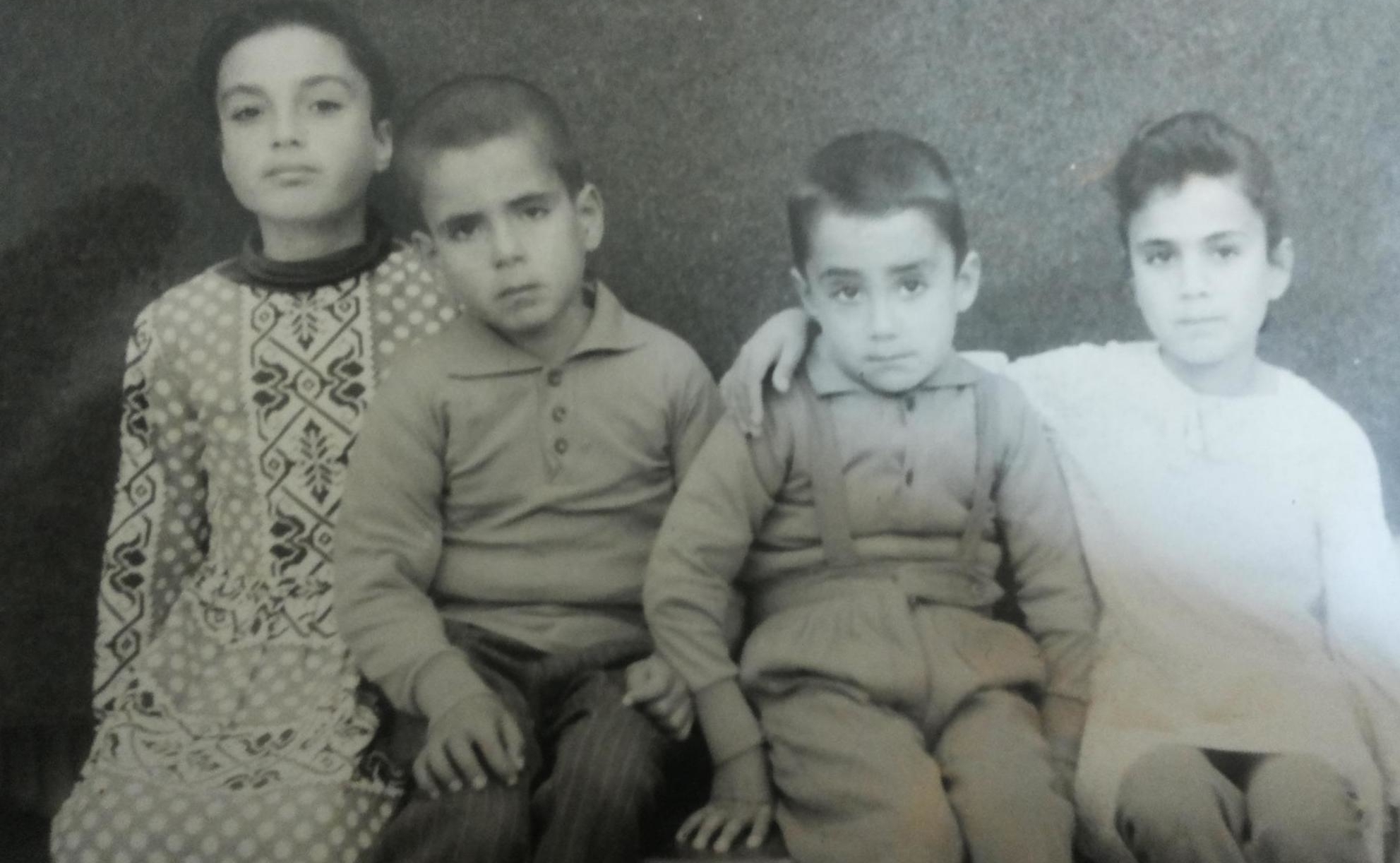

Over the following five years, my grandmother applied for a family reunion permit and each time she was refused. Finally, my grandmother visited the Israeli militant leader, Abu Sabri, who governed the area at the time, and pleaded with him to take pity on her family. "Look at him," she said in a brittle voice, pointing at my youngest uncle, Atef. "He is 8 years old and he has never seen his father. Not even once." My grandmother hoped Abu Sabri would be moved. He was not.

Despite the rejections, my grandmother still clung to hope. Once, my mother went with her to see Abu Sabri. As usual, he rejected their application. Just as they turned to go back home, my mother, 11 years old, stopped and asked the Israeli leader: "Don’t you have children, sir? Could you live without them?" In less than two days, my mother says, the permit was finally approved. After eight years of separation, her father was coming home.

My mother Imprisoned

My mother was 19 years old when she travelled to Ramallah to earn a diploma in dressmaking and design. While studying, she visited Jenin, Hebron, Jerusalem and Tiberias.

She prayed in the Al-Aqsa and Al-Ibrahim mosques. She swam in Tiberias Lake and the Dead Sea. When she talks about these times, her voice is tinged with longing. Life was much easier then, she says. Palestinians could travel so easily.

One day, there was a demonstration against the occupation in Ramallah. The girls of the academy had been throwing stones, and one soldier was hit in the head. His injury was serious. The soldiers dispersed the crowd, then began arresting the girls. My mother and some others escaped into the academy.

My mother was scared. She was in a classroom, hiding in a narrow space beside a sewing machine. She remembers a curtain in front of her and a garbage bin. She heard the other girls screaming. "But I didn’t move," she says.

Holding her breath, trying not to make a sound, my mother squatted, thinking she was about to spend the night alone, with no food or blanket to keep the cold away. Suddenly she heard footsteps. My mother remembers her heart beating so fast. She didn’t want to go to prison. Her eyes widened. It was not a soldier. It was her teacher.

"You're here!" my mother's teacher exclaimed. "Why didn’t you tell me? I could have hidden you!" At that moment, a soldier appeared behind her like a ghost, screaming in broken Arabic, badik tkhabiha! (you're trying to hide her). Before my mother's teacher could even turn around, the soldier hit her in the head with his rifle and she fell to the ground, unconscious.

Fear washed over my mother as the soldier stared at her with his sharp eyes. He pulled her up by her elbow, dragging her to join the other girls. She stood silent, eyeing a spot on her shoes, praying to God to help her. He did. Although 20 girls were dragged to the jeep, all accused of throwing stones, they didn’t stay in prison long. The academy managed to collect money from charity institutions to bail them out and my mom, a teenage prisoner, was released.

To Saudi Arabia and back

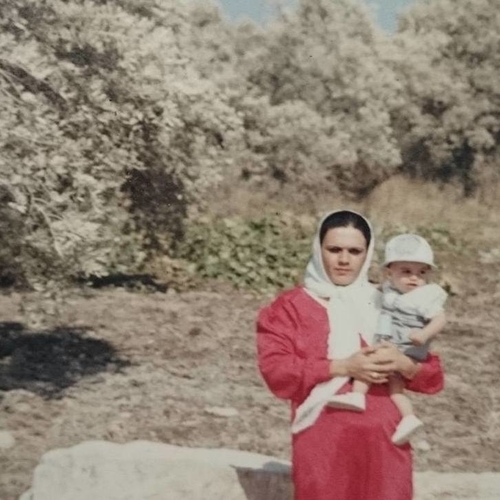

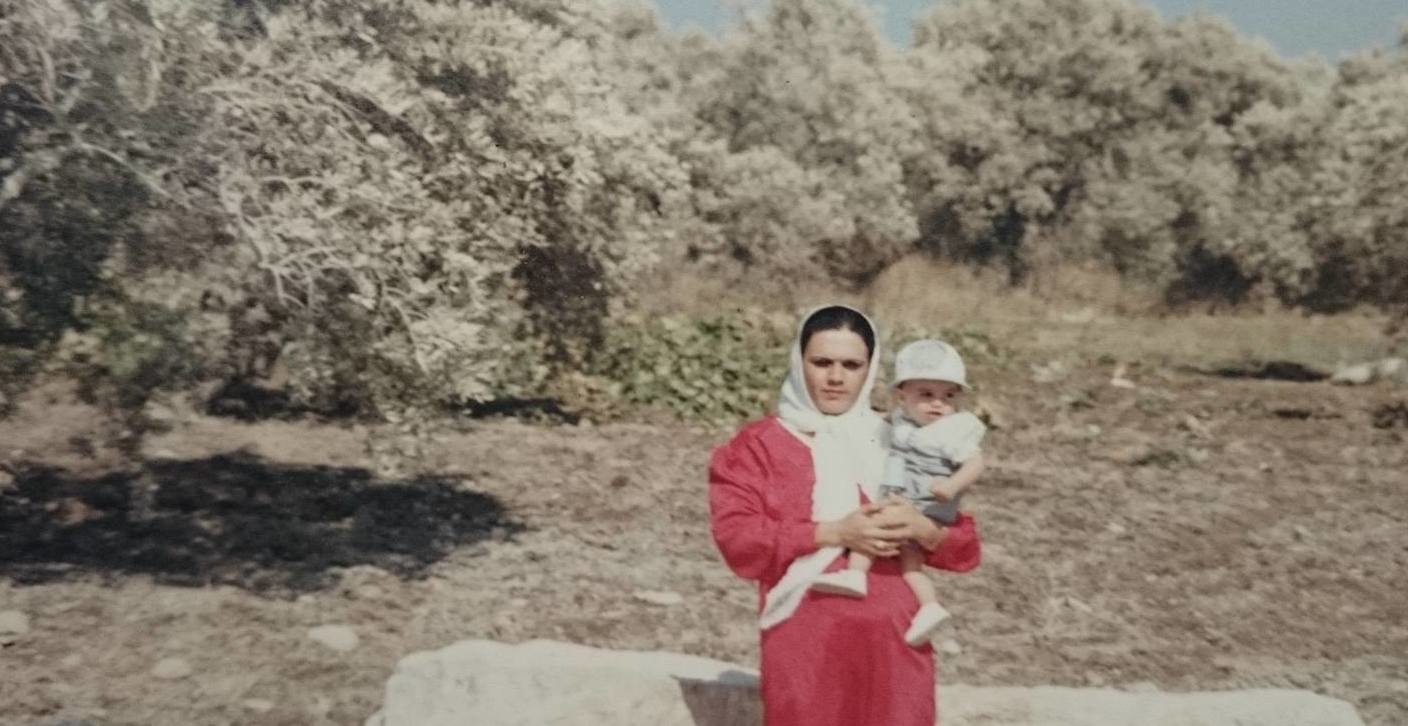

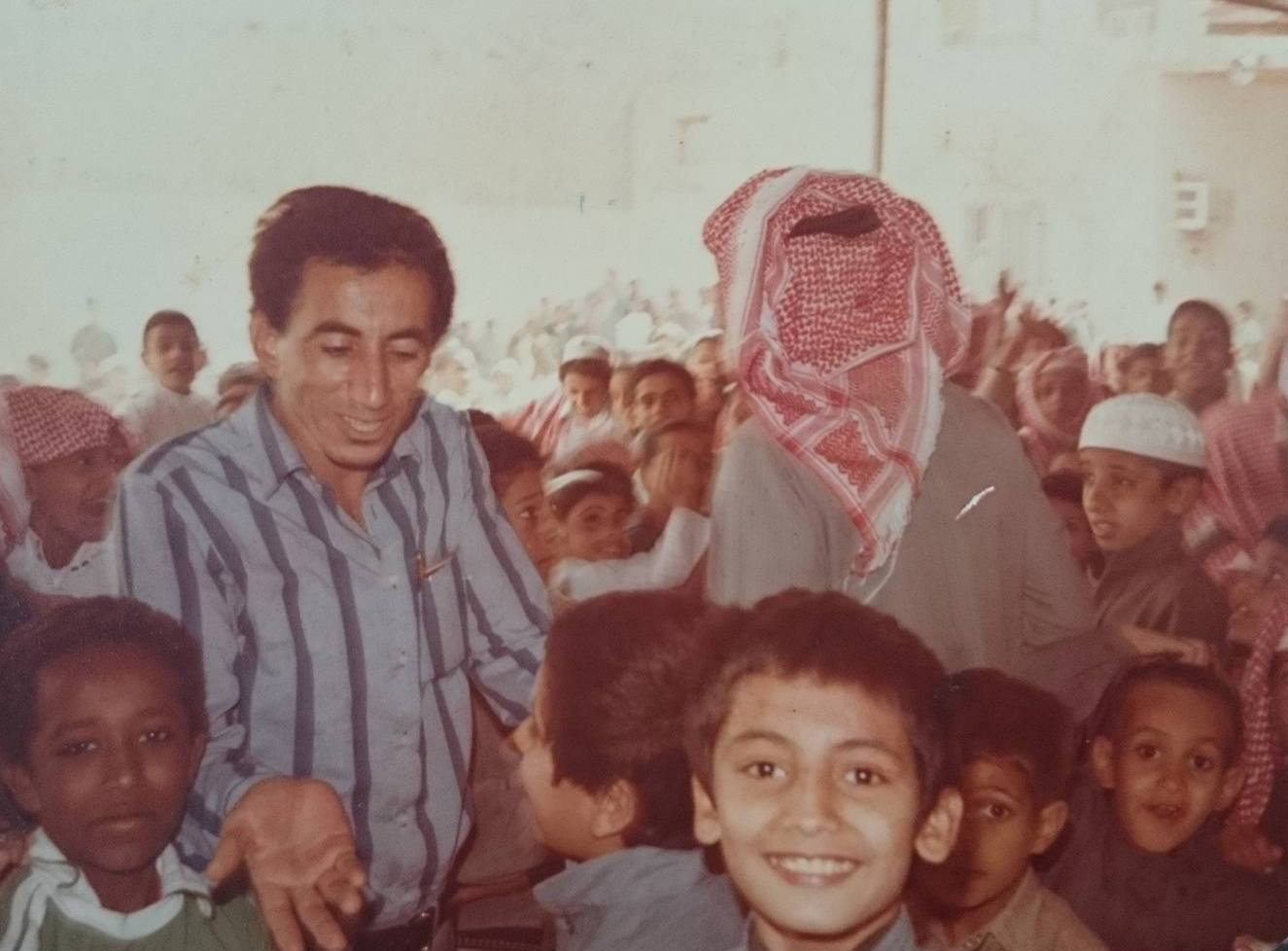

Later, during the 1980s-90s after my mother was married, my family lived in Saudi Arabia, where my father had found a better job as a science teacher. My mother taught reading and

writing to young children at home. She says they had a beautiful house and were very happy.

But each time a Saudi national was found to replace my dad in a school, his contract was terminated. So we moved from one city to another, until in 1996 the Saudi government initiated a policy of “Saudization,” replacing foreign workers with Saudi nationals. That meant my father, along with hundreds of Palestinian workers, were forced to return to Gaza. Just a few months after my birth, my family found themselves at the Allenby crossing, between Jordan and the occupied West Bank, on our way home.

It was June. The Allenby crossing was crowded with people coming and going. My mother remembers the smell of perfume mixed with sweat, the shouted commands of the Israeli guards, the cool breeze she’d missed while living in the extreme heat of Saudi Arabia. Finally, she was ordered into the inspection room. First her suitcases were searched. Then she was strip-searched.

My mother was familiar with the humiliating procedures Palestinians are subjected to at our borders, but that didn’t make it any less difficult. Her voice still shakes as she tells the story, describes the feeling of being treated as less than human.

The Israeli guards were confused when they noticed traces of stitches on my mother's belly. They scanned the spot with a special machine a dozen times. My mother told them again how she'd had an appendectomy some years before.

The guards finally sent her out, as she held me to her chest. My 3-year-old sister was crying, unwilling to push through the crowd. My mother leaned over, pulling my sister up from her armpit. A female guard shouted, "Baby, baby!" She took my sister from my mother and held her carefully between her arms, trying to calm her. Then she passed my sister back to my mother and said, "Don’t hold her like that. She is very young."

My mother's stories

My mother was the "tranquilizer" for our family. While Israel bombed us during the summer of 2014, my mother told me stories to help me forget my fears. She told me how I looked when I was young and how one time I got lost in Jabalia Camp after I followed my brother there at night. How I fell on my face at my cousin's wedding and broke my nose. How one of my teachers sent a letter home complaining that I was so naughty. "Your teacher said you were jumping on the benches, making a huge mess in the class," Mom reminds me, grinning.

During those scary times, my mother used to call my married sister on the phone—almost every day— to entertain her young grandson. She told Ahmed stories about a duck and her ducklings, a wolf and the sheep he preyed on, and a smart goldfish named (you guessed it) Ahmed. Whenever a bomb exploded, my mother told Ahmed it was the sound of thunder or fireworks. And he believed her.

There were 51 days of death, terror and displacement—the drones buzzing overhead, the sound of bombs every now and then, the smell of explosives penetrating the flat. Fear clutched at our hearts. My mom, too, was afraid, mostly for our safety. She insisted that my brothers stay at home from work. She saw the bodies on TV, the young men hit by warplanes. She imagined the moment their souls rose to their creator, their families receiving the news of their deaths. My mother agonized over the thought of losing one of her sons. And when my brothers left the house—one to Al-Shifa Hospital and the other to Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights—my mother sat praying for hours, asking God to keep them from harm.

My mom refuses to call herself a hero, however. She sees herself differently. "I am simply a Palestinian mother."