Deep down in my mother’s closet lay a box of photos from when she was a child. The stories and memories hidden in those old photos mean nothing to most people, but they mean everything to me and my family. My parents, who are from Gaza, moved to Abu Dhabi soon after they got married. As a child, I would often look through those pictures and imagine my homeland as it was back then.

But the idyllic vision of Gaza I created in my mind was shattered when my family and I spent a summer there when I was 9 years old. During that trip, I grew to love my homeland despite the injustices and hardships.

Exile bedtime stories

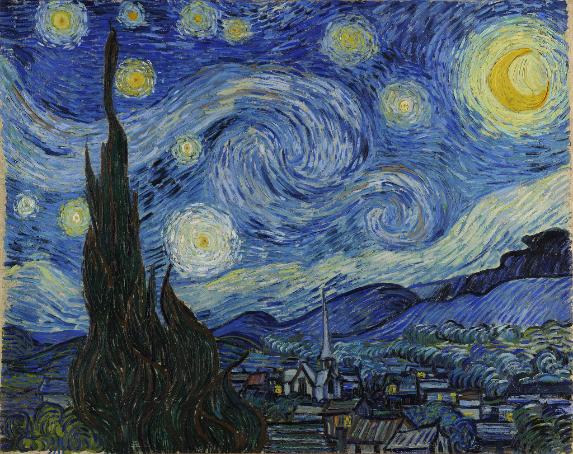

My infatuation with Gaza began when I was eight years old. I would often stare at photos from that box and ask my mother to tell me about them. Her stories became part of my bedtime ritual. One night I remember mumbling in my sleepy voice, “What was our homeland like when you were my age, mama?”

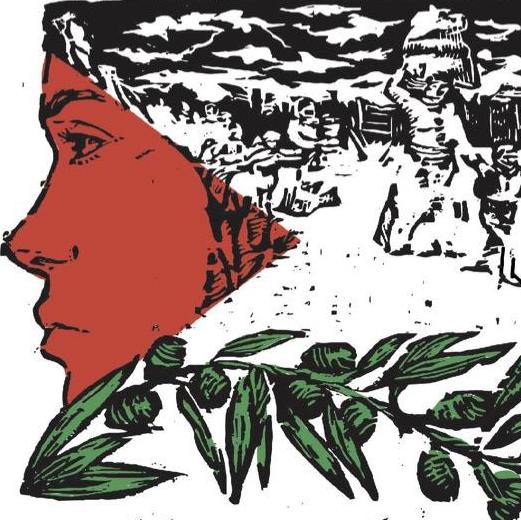

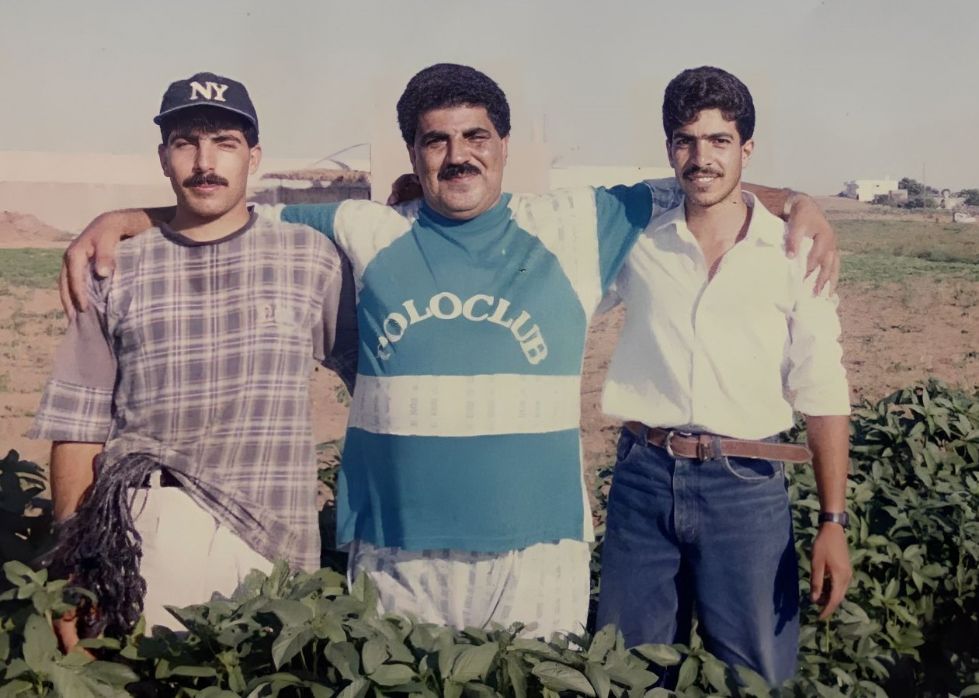

My mother sighed and answered, “It was a boundless green land filled with olive and orange trees. They used to call your grandfather the King of Citrus, since his land produced huge amounts of juicy fresh oranges and lemons. Every afternoon, your aunts and I would help harvest those citrus crops. We barely had enough time to change out of our school uniforms. We had to take responsibility at a very young age since your uncles weren’t born yet. We used to go in the early morning to water the trees. Often we would run into Israeli soldiers.”

“Were they armed?” I asked. “Did they ever hurt you?”

“They were armed all the time, but they were occupied running after Palestinian rebels. I once saw them pointing their guns at some young men, but we couldn’t stop to see what happened. I remember seeing a hoopoe sitting peacefully on a branch and then flying away in a heartbeat at the sound of gunfire.”

“Did the soldiers kill the young men?” My mother didn’t know.

“So, you went to school and worked on grandpa’s land at the same time?” I asked, changing the subject.

“Yes, and actually, most of my peers also worked and went to school,” she said, shifting her eyes in an attempt to hide from me things my eight-year-old self was not ready to hear.

I asked my mother whether she had enough time to study. “No,” she answered. “School was not our priority 30 years ago. Working the land and harvesting the fruit and vegetables always came first. Exporting crops to other cities and countries was the main source of income for many families. Traders would buy the crops from the local farmers — including my father — and travel all around Palestine by car or train selling them.

When I suggested that Gaza must have changed by now, my mother responded, “Yeah, it changed.”

Her response made me want to know why her stories were only about Gaza from three decades ago. I wanted to know what it was like there now. Does Gaza of today look like Abu Dhabi? Is every inch covered by skyscrapers? Does Gaza have malls, amusement parks, public parks, and wide deserts for camping and riding quad bikes like in Abu Dhabi?

Visiting Gaza for the first time

In the summer of 2012, my parents surprised me with the news that we would be vacationing in Gaza! It was going to be my first visit ever. I was excited to be going to Gaza, but when I learned we would be flying to Egypt and then driving to Gaza, I could not understand why we didn’t just fly there directly. I was beginning to come face to face with the reality I had spent years wondering about.

During the ride that took us from one Egyptian checkpoint to another, I discovered that Gaza has no airport because it was destroyed by the Israeli military between December 2001 and January 2002, after the Second Intifada, and never rebuilt. Because of that, we had to drive in cars and buses for ten hours without taking a rest until we reached my grandfather’s house in the middle of Gaza City.

In my first few minutes there I understood why I had never been satisfied with my mother’s answers to my questions about Gaza. The only way to understand Gaza is to go there. Right away, I could see that Gaza was no longer a “boundless” land. It was a land surrounded by checkpoints and borders. Just to be allowed into Gaza we had to undergo questioning by police officers and other time-consuming procedures. The process of going in or out of Gaza felt like entering or leaving prison.

For the first few weeks, I did not like being in Gaza. My parents, grandfather, aunts, uncles, and cousins seemed to share a special bond. They felt at home, while I felt lonely and isolated.

My mother was right; many things about Gaza had changed over the past 30 years. There were no Israeli soldiers roaming the city. Men were not being murdered in the streets. Other things had changed, too, but not in the ways I had imagined. Rather than being boundless, everything in Gaza was limited, including electricity, fresh water, and job opportunities.

I didn’t see Israeli soldiers because they were just beyond the wall that surrounds Gaza, preventing people and crops from moving an inch beyond borders set by Israel. Those borders make it impossible for my generation to visit other parts of Palestine.

Israeli soldiers do not kill Gazans in the streets anymore. Instead, they kill us with missiles and rockets while we are sleeping in our beds. Although we did not experience an Israeli attack during our vacation, it was impossible for a family gathering not to include a “war chat” during which everyone shared a memory from a past Israeli attack. During one of these chats, I learned that a cousin I did not know about had been killed when he was 16 because of war remnants. He was killed along with his friend when an unexploded bomb from a previous attack detonated.

As for my aunts, they no longer work in my grandfather’s citrus groves. Now their sons do. But unlike my aunts, my cousins do not have the privilege of continuing their education beyond middle school, since their families need them to work in the groves. My cousins are luckier than many young Gazans. I was shocked to see many children my age and younger selling everything from clothes to mint on the streets to help support their families.

One boy, in particular, stands out. I saw him standing in front of a hospital, selling candies to passersby. He was most probably of elementary school age, dressed in rags, with shaggy hair. Most people walked by without buying any candy. It is not right that so many children in Gaza must sell candy and other items on the street just to survive. Gazan children should be able to enjoy their childhood.

Falling in love with Gaza

Two weeks into our visit, I found myself better able to cope with the situation in my beloved but wounded country. I learned to see the beauty of the pale streets and cracked buildings. I learned to have fun playing hopscotch with my cousins instead of spending hours in a huge mall and then feeling lonely once I got home. I started developing a mysterious bond with everything around me.

Those couple of months taught me to appreciate the beauty of this land. After living as a foreigner in someone else’s country, I finally felt like l belonged. I learned how to be happy with the smallest things Gaza offered: playing games with my cousins, eating a peach my uncle picked from one of his trees, enjoying a family lunch, and creating shared memories with my family. These things became more than enough for me.

I burst into tears the day we left Gaza. As we drove away, I looked through the car window and thought about everything we were leaving behind. Even after we were back in Abu Dhabi, I could not get Gaza out of my mind; I thought about it every day.

It turned out that my parents felt the same way. A year later we made the biggest decision of our lives. We decided to abandon our life in exile and return to the only place we truly belong. We realized that despite the hardships of living in Gaza, nothing in the world is worth leaving our homeland.

We moved to Gaza for good in 2013 and never looked back.