One day at school, our teacher entered the classroom, barely managing to mumble some words because he had been running up the stairs. He was trying to tell us that we should get home as fast as possible and gave no further explanation.

I packed my precious items: my books, my coloring books, and a pencil with a ballerina on it that my mum gave to me as a first-year-of-school gift. Then I rushed from the classroom out into the corridor just like the others to witness the first tragic scene in my five years of life, which has never left me alone since.

The school stairs were brimming with people in a way that filled me with dread. Students and teachers were running and shouting from every corner; the stairs looked so tight, so dark, and so throttling.

Although looking at the stairwell in those few seconds made me feel as if I were choking, I never hesitated to take one step forward to join the streaming crowd. I merged with the flood and, due to the pushing, did not make any physical effort descending the stairs. With all the pushing, one of my colleagues fell down the stairs and scraped his head. I saw drops of blood spill from his head, staining the white floor, and with it my innocent, babyish, soft worldview ended. It was the first time I saw blood pouring out of a person, but it would not be the last. I helped him and we rushed together to the bus.

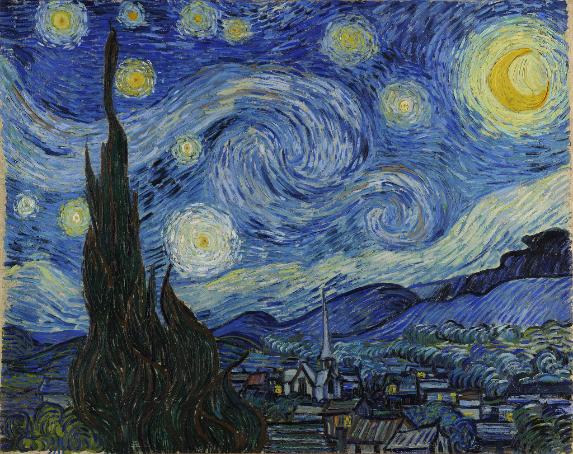

At that age, I loved school so much, and I loved science the most. I watched Sid the Science Kid every day (in the Arabic version of the show, his name is Zayd) and I loved Nina’s Lab. My favorite cartoons always depicted the moon as a ball made of cheese. I couldn’t accept this idea because I believed that the sun’s rays probably hit the moon — if it’s cheese, I thought, it would melt onto neighboring stars.

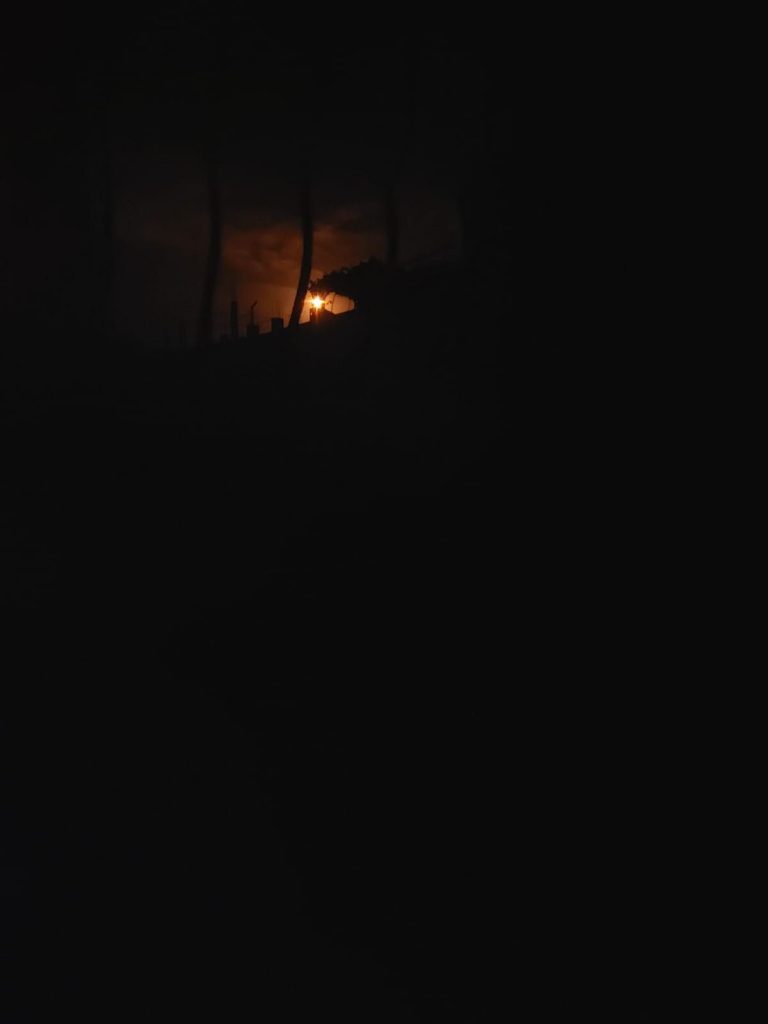

I stayed home too many times after that terrifying day, playing hide and seek. Sometimes I hid from the recurring, deafening explosions, and other times I played my favorite game, which was imagining I was an astronaut and the orangey, reddish color flashing before my eyes through the window was the stars visiting me. I loved the sky, the moon, and the stars, and dreamed of a magical elixir that transforms humans to birds whenever we want. I knew that was impossible, however, so I soon went back to imagining more logical things, like becoming an astronaut.

One night, while my large extended family was gathered in our basement apartment, we children were playing hide and seek, as usual, hiding from the sound of bombs. We were seeking the safest, warmest spot to practice our roles as children in another imaginary world, pretending together, when my cousin informed me that the recurrent explosions were rockets being thrown on people’s homes. But how could this be true? Nina and the Neurons had taught me that rockets are sent to the moon, to the planets in outer space, not people’s homes! My five-year-old brain took so long to grasp this brand-new concept — the concept of cruelty and horror. At that age, I began to recognize new types of rockets: death rockets, devil rockets.

The rocket attacks lasted for weeks and caused a huge loss that was beyond my understanding at the time. When the recurrent explosions finally stopped, we had to go back to school. Streets were much different from how they had been before: dark, ashy, and melancholic. Scenes of destruction were everywhere! I was surprised to see that my school had become a bunch of huge white tents surrounded by cameras. I thought it was a kind of play or theatrical production our teachers created, so I didn’t care much. When I came back home, my dad stated that he had seen me on TV. I said that I’d seen cameras but didn’t understand why, and my dad explained that the Israeli military had bombed the school. It was then I knew the powdery ashes I’d seen were my school’s former walls.

Gazan children grow up very fast, and some of us know the bitter taste of the agony of loss before the sweet taste of soft dreams; death hunts Gaza, our memories, and us. And if it doesn’t kill us, it kills our dreams. The toughest experience one can go through here is being in charge of a child. It is hard to comfort a child, knowing too well that you were once a child and were exposed to the same trauma, during war. I always wanted to teach my little sister, Nour, art, science, languages, and how to create her own imaginary world before war teaches her the cruel corrupt reality of us. Because she is, as Wordsworth once said,

“a simple Child,

“a simple Child,

That lightly draws its breath,

And feels its life in every limb,

What should it know of death?”

But when it was bedtime, two wars ago, and she couldn’t sleep, frightened with the darkness that seized the neighborhood and the calmness that made the zzzz buzzing sound that drones make, breaking through to my bones, I decided to narrate to my five-year-old sister the story of the Little Prince. As the explosions outside got louder and louder and crimson caught the sky with its bloody color, I couldn’t help but lie to her and say it was a star, just like I used to tell myself when I was her age. I tried to convince her, just like how I tried to convince my younger self, that they were just “stars,” the same stars I counted every night and wished for something new before sleep. Anyway, I stopped counting stars but I kept wishing every night for all children, our children, my baby sister, peace and joy.