September

The morning after the graduation ceremony is somehow different. Before, I was focused on my studies. After the final exams and papers, my focus turned to the ceremony and my family’s joy at my accomplishment. I finally completed a long journey and reached my destination. I had reached the light at the end of the tunnel.

But now I am sitting in bed, rubbing my eyes and chasing away anxious dreams. I’m overcome by a letdown feeling.

What do I do now? What’s next?

Should I apply to a master’s program or enhance my professional skills and look for a job? I consider the details of each option for a long time. Indecisiveness overwhelms me, and I flop down on my pillow.

October

Somehow, I do not surrender to the hopelessness of reality. I follow both paths! I dare to try!

I apply to several universities outside Gaza for programs in translation and intercultural studies. At the same time, I enroll in courses at local organizations, to improve my translation and communication skills.

November

The university applications are done and sent!

February

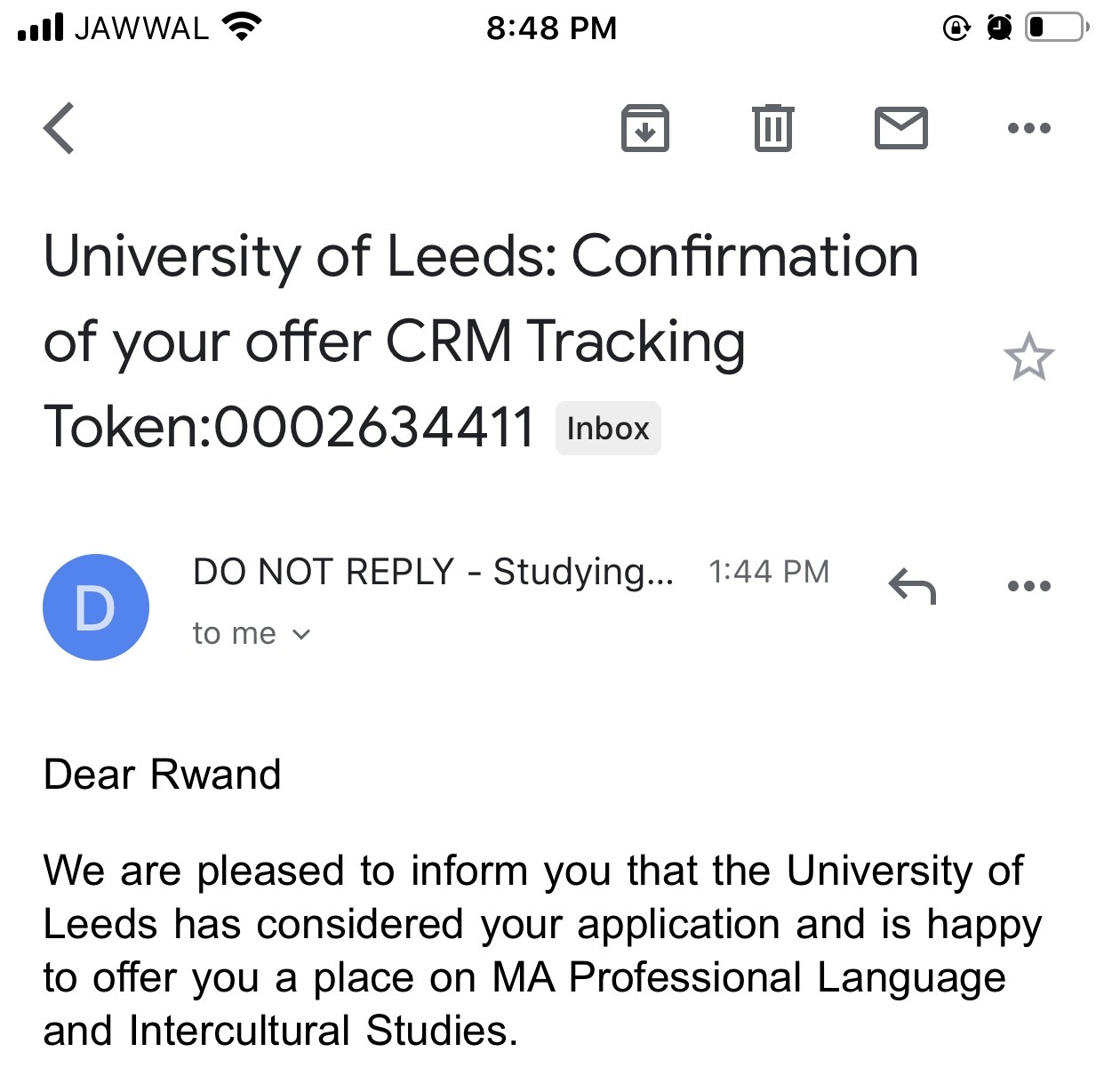

I receive acceptances from three universities, but they are all conditional—meaning I have to take additional courses and pass more tests. And in a crushing disappointment, my application to become a Chevening scholar is rejected. Chevening would have provided the funds for me to study at a university in the United Kingdom.

Everything I had built, planned for, fought for, fretted over and dreamed of seemed to be a mirage that moves ever further as I draw close.

My mother comes into my room as tears pour down my face. She pulls a wrinkled handkerchief out of her sleeve and wipes my puffy cheeks. She assures me that one day I will achieve what I pursue. But I am oblivious. All I can think about is this setback and the hard work required to move forward with my life.

I will have to take prerequisite courses and pass the English proficiency tests to convert the conditional offers into full acceptance. But I can do that; I am a hard worker. But without Chevening, I also need to pull together funding for tuition, books, lodging, travel and living expenses.

I will need to get a new passport. I will need to arrange to get to England. I will have to persuade Israeli officials I am not a criminal, convicted felon, smuggler or vandal. I will have to stay off the Israeli blacklist. Only then can I hope to cross the borders they keep closed.

If and when I get to England, I will have to persuade my fellow students to not see me as a stereotype, to not think of me as a terrorist or hardline factionalist.

It's too much to think about all at once.

March

COVID-19 threatens Gaza. No outings, no family gatherings, no training classes. On a last trip to the market, I found empty shelves, a few tinned goods, some hand sanitizer. We are all concerned about the virus because of the scarcity of medical equipment and supplies.

I have ample time to indulge in Netflix or work from bed and roam in bunny slippers all day. Such unbridled laziness sounds fun, but I’m getting nothing done.

My life alternates between moments of complete boredom and frivolous delight playing puzzle games on my mobile phone.

I spend countless hours watching the Spanish TV series, La Casa De Papal (The Money Heist) and TikTok compilations. My eyes hurt and I feel like a sloth.

April

I have an epiphany: This is a special time I can use to try new things, to have new experiences.

I figure out how to use my phone, laptop and smartwatch to stay brisk and energetic when life's normal schedules have disappeared.

I discover that an energetic morning kicks off with a strong bedtime routine the night before. I activate and turn on the Do Not Disturb mode on my phone, so my sleep is not interrupted. I set the alarm so my phone will wake me up in the morning.

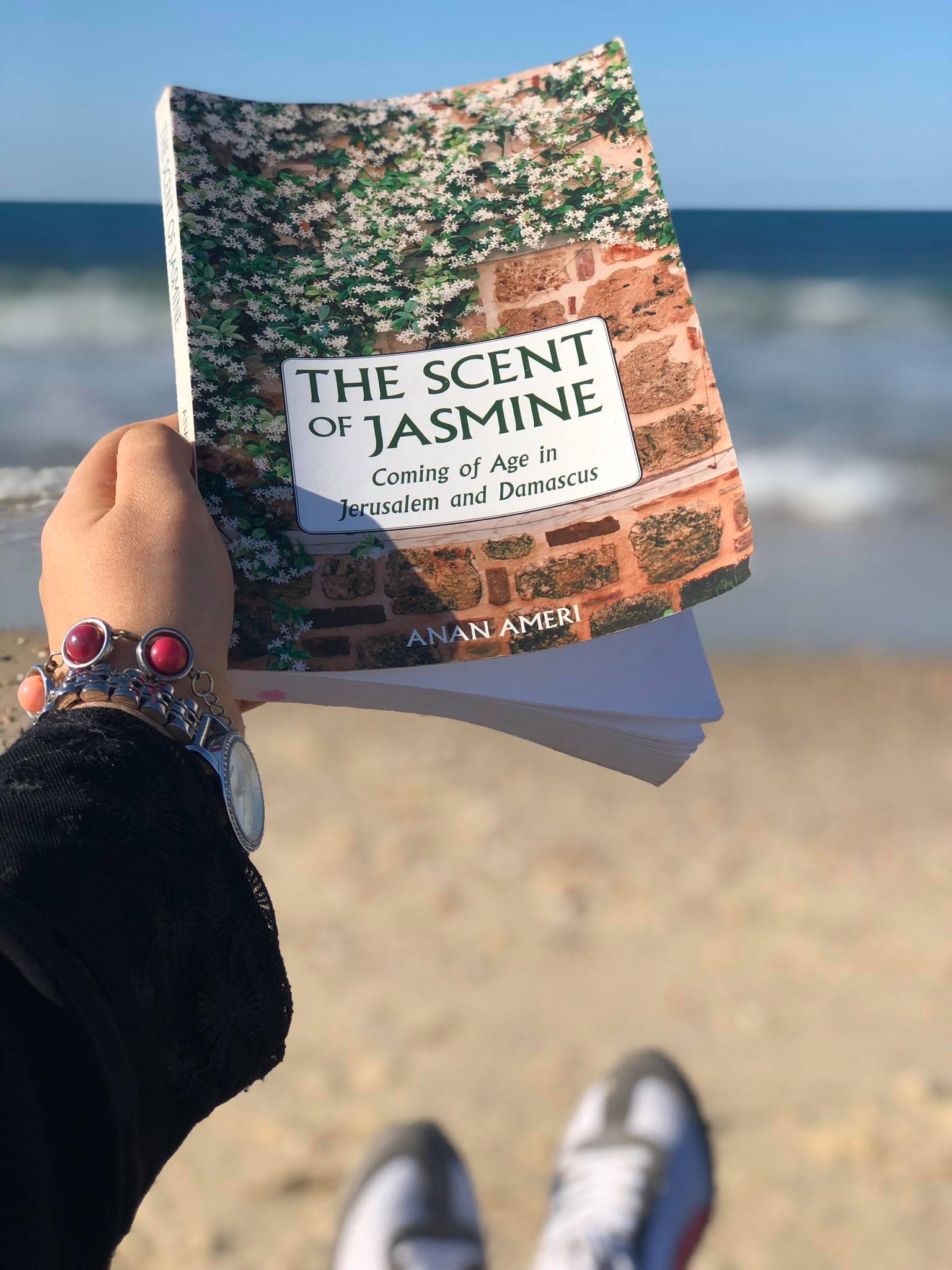

I decide to take up a hobby—reading books that have received good reviews. I firmly believe in the healing power of reading and writing. I read success stories and motivational self-help guides. I love “The Kite Runner” by Khaled Hussein. I relate to the story of the young boy who stands up for himself. “The Land of the Sad Oranges” by the iconic Palestinian writer Ghassan Kanafani makes me cry. It is hard to read his stories of the forced displacement of the Palestinian people. I highlight and jot down meaningful passages.

May

I can’t stay upbeat and on task all the time. Every once in a while, bleakness overwhelms me. I can’t resist these dark moments. It’s like I bump into a rock and fall into thorns.

The sun invades my room through lace curtains, telling me it is time to get up. But I think instead of how hard I worked to earn my university degree. I spared no effort to achieve great results on my exams. I completed voluntary training so my applications would stand out, and I obtained recommendations. Yet here I am, making no progress.

I feel as though I am a wounded bird, falling instead of flying.

June

My life is at a stalemate.

Some days I don't know which way to walk. I can't find a wall to lean on.

I am like so many Palestinian university graduates. Disappointment stalks and paralyzes us. Our ambitions and pursuits scatter. The wind blows away our aspirations, which become mere memories.

But sometimes, the morning breeze tells me something different: “There is light at the end of the tunnel.”

I have taken on work in translation. This keeps me busy for many hours.

In better moments, I see that the logic of life is this: There is strength after depression, healing after disease, livelihood after poverty. Sometimes we get sick, then heal; we grieve, then rejoice. Sadness is not permanent. We must remain patient until God blesses us.

I muster my courage. I wipe my tears with my palms. A hidden voice says, “Don't quit! When you see a ray of light, cling to it and do not give up until you reach your goal. If you can’t climb one ladder, find a different one."

Then I sink back into my weakness, wondering, “Is there` a light at the end of the tunnel?”