It was the last day of Ramadan, but rather than being awash with peace and contemplation, I was lost in a sea of despair.

My mother and I were preparing to celebrate Eid al-Fitr (a Muslim holiday that marks the end of fasting), along with the rest of the family. I thought of my late sister, Rasha. To distract myself from these sad thoughts, I scrolled through Facebook posts from people celebrating their first Eid with loved ones, like newborns. I became incensed by one person who wrote, “It is not Eid unless your loved ones are present.” It made me think of my mother. This would be her first Eid without Rasha.

There is no special word in English for a parent who has lost a daughter, nothing like the word “widow” or “widower,” but there is a word in Arabic. The word is “thakla” (ثكلى), which means “bereaved mother.” It is a label for the unthinkable, a parent who outlives her child.

On this last day of Ramadan, my mother was a “thakla.” Her daughter and my sister, Rasha, would not be present. The daughter with cerebral palsy who my mother raised for 19 years—gone. The child she nurtured—gone. The flower my mother watered—gone.

Whenever my mother fed Rasha she would say, "Rasha ate and I am stuffed.” Her child’s appetite was satisfied, so she also was fulfilled.

On this particular evening before our first Eid al-Fitr without Rasha, my mother prepared the house for the next day’s revelry. In the meantime, I kneaded the dough for the special holiday dessert kaak. Then I heard my brother shout for me to come to my mother. I found her sobbing with her head in her hands. “Malik yamma?” I asked. (“What’s going on?”) Slowly, my mother dropped her arms and whispered something. I discerned just two words: “Eid” and “Rasha.” We were all in mourning.

Her cheeks wet with tears as I held her in my arms, my mother insisted that preparations for Eid continue and asked that I take the bread out of the fridge for the next day’s breakfast. Later, as I worked in the kitchen to shape the dough for the kaak, I thought, “It's okay to mourn.”

My younger brother tried to mask our sorrow. He recited the Eid prayers throughout the house while I went on making the cookies.

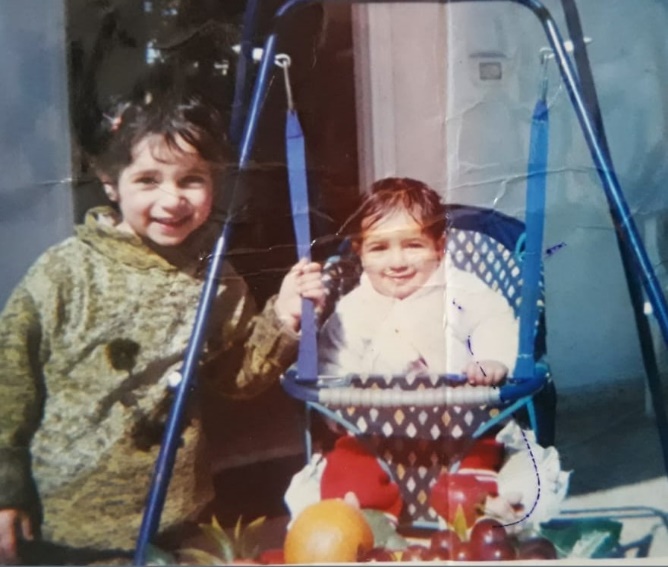

The aroma of the baking kaak reminded me of past Eids. In previous years, we bought new clothes, especially for Rasha, awoke early, showered and dressed her, combed her hair, dabbed the best perfume on her dress and then prepared the food for the day’s celebration. This Eid would be the first time I didn't give Rasha sweets and then run off, earning my mother's rebukes for doing so. "Don’t you have the patience to sit beside her and help her eat?” my mother would ask. This Eid I wouldn’t experience such moments with Rasha. I wondered, will that make the day more enjoyable? I knew it wouldn’t.

Going on with the preparations, I wrapped the kaak without setting aside some for Rasha as I used to do. This very act made it harder for me to deflect the sad thoughts. When people think of cerebral palsy, the images that usually come to mind are jerky muscle movements and poor balance. But it’s also often accompanied by autism and other developmental disabilities, as well as shortened lifespans. Over the years, it was heartbreaking to witness Rasha’s health deteriorate, her face become increasingly pale, her smile fade and her ability to move diminish. She became a shadow of herself—the girl who smiled and laughed so big and heartily when my parents sang to her, or when I tickled her and called her “Rashrash.”

The last Eid with Rasha, we changed things up a bit. It was really hard to take Rasha out of the house on trips, but I decided that time we should all participate in the family festivities. We even visited our grandmother in Rafah, which is quite far away. But the day was bittersweet. When we sat beside each other during the car ride to grandmother’s home, I was shocked to realize how much Rasha’s health had deteriorated. She no longer smiled at the camera and was terribly thin, her legs thin as a twigs compared to mine. I felt something ominous might happen, but I didn’t anticipate she would die.

I was lost and confused when I first arrived home from college after learning Rasha was in the hospital. Rasha could barely breathe as I sat by her bedside that day. Then she collapsed in my mother’s hands and passed away very peacefully. I was tortured by mom's shrieks, calling out to Rasha repeatedly, but soothed by my father’s hugs. When I finally kissed my sister’s cold cheeks and left the room, my baba (father) asked me, “Do you feel empty without her?” I could only burst into tears in reply. We were just two years apart in age, yet she was gone.

After the funeral, I prayed, trusting in the mercy of Allah. Allah, grant me a tranquil mind. To you, I leave all of life’s strife. You are the Almighty. That which you have taken from us is already yours. Rasha is your guest. Please be generous with her and please help all of us who mourn her passing. Have mercy on us.

It was a blessing to pray. I released all the fragments of my shattered heart in one sajda (a part of our prayer in which we feel we are closest to Allah). I felt serene and knew Rasha’s soul was now at peace as I bowed down, my face and palms touched the earth.