I’ve always wanted to grow my hair long, but my father, because of social expectations, thinks it’s inappropriate for a guy. When I was young, my hair was thick, soft and straight. But because of Gaza’s polluted, salty water, it started to dry out and curl. I transformed from the kid with nice hair to the guy with scary hair; kids stared when they saw me on the street. “The one with hair” is who I am. I even sport a small hair bun now, although I untie it when I go out, simply because Gaza society isn’t ready for that.

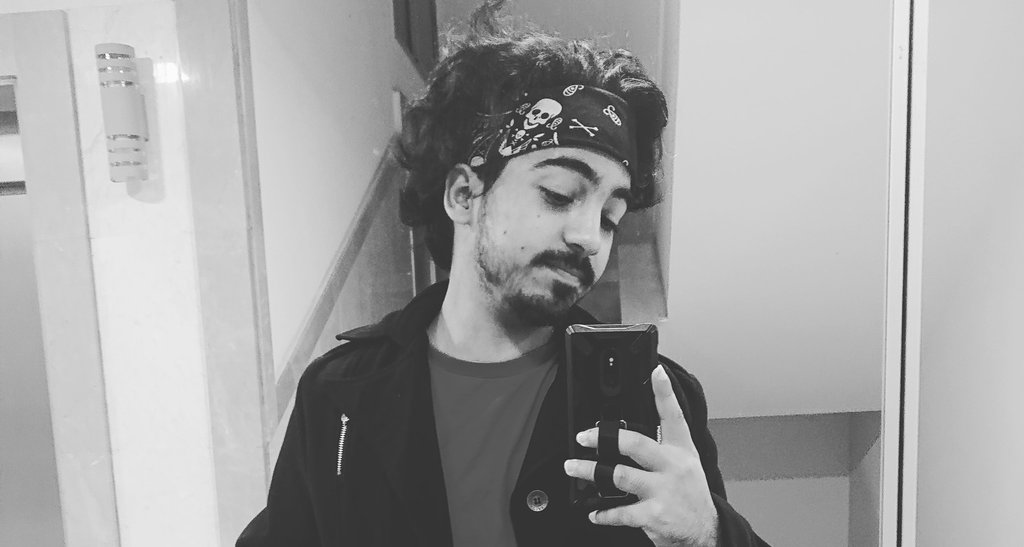

Recently, I let it grow even longer and I justified it to my father by warning that I might catch the coronavirus at a barbershop. Of course, that’s a lie; I’ve only gone to a barbershop twice since I returned to Gaza from the United States on December 25, 2016. But it’s my identity now: the dude with long, black hair.

I remember both times at the barber very well. The first was when I had just returned to Gaza. My hair was long because during my five months in the U.S., I hadn’t cut my hair (except some trimming I did myself). My dad couldn’t tolerate it, so sent me straight to have a haircut the next day. The second time was in 2019. I cut my hair at home myself, and I mistakenly shortened it too much in the back because I could not see very well, so I needed a professional barber to “fix” it.

Almost no one in Gaza cuts their hair at home. Haircuts are very cheap in Gaza, unlike in the U.S. Children can get a haircut for a dollar, and teenagers pay $2. As for men, they can get professional haircuts for less than $3. Of course, for females, the prices are higher, as is almost everything else, like clothing.

Another reason people in Gaza don’t cut their hair themselves is the cost of buying a hair clipper, and the electricity needed for the types that do the best job. Gaza’s constant power outages force us to prioritize housework and other vital tasks when we’re fortunate enough to have electricity. And then there’s the need to learn how to cut hair, particularly your own. Talking from experience, I can say it’s not so easy!

But I decided to try, and I’ve gotten better over time. Almost no one can tell I do it myself. Yet I also love my hair when it’s messy. To me, it is not just hair; it is a part of who I am as a person. This wild, black hair is my Arab identity. The same is true for my father. He was called, “the Korean guy” in his youth because of his distinctive hair.

The first time I linked my hair with my identity was in May 2019, when We Are Not Numbers organized its singing contest GazaVision. My fellow writer Omnia Ghassan told me she loved my messy hair, or maybe I should say my “riot” hair. Other people had probably said that before, but it seemed different that day. A huge event like GazaVision is unusual in Gaza, and singing isn’t common either. It was unique, and I definitely felt unique with my long, messy, black hair. I took a selfie on that day with my friend, Noor Al Yacoubi’s, iPhone. It is one of my favorite selfies of all time, and it is hanging on the wall at WANN’s office.

Still, not all is good with my hair. I am 22 and my hair is already turning gray. It started when I was 18. I was a senior in high school, the tawjihi year that determines what university you can attend and what you can study. Due to the huge pressure, I think, the first gray hair showed up. After four years of university, you can imagine full of gray my head is now! I hated it at first, but now I love it. I’ve started to accept it, since many people told me gray hair means wisdom; whether it’s true or not, it makes me feel sort of distinctive.

So many young people get gray hair here, though, so it won’t be true for long. There may be genetic reasons, but it’s different in Gaza. I believe the main reason people gray early here is fear and stress. It’s partially from the repeated, brutal Israeli wars on Gaza. But there is so much more feeding the fear. Most college students fear unemployment after they graduate, for instance. I was, and still partially am, one of those people. (I am employed only part time by We Are Not Numbers.) The unemployment rate among youths here is about 70%, including among holders of master’s and Ph.D. degrees.

Listing all of the reasons why we are depressed and turning gray here would require a book. Maybe it’s one that should be written; maybe these simple stories of fear and gray hair will penetrate more than politics can.