On the first day of eighth grade, I met a girl whose haughty expression shifted abruptly when she heard the principal ask our teacher, “How is the Saudi Arabian girl doing?”

“Are you from Saudi Arabia?” Her shock at encountering someone who had lived outside the prison that is Gaza chased away her aloofness. I answered “yes,” and it was only the first such patient “yes” I have had to utter during the past eight years I’ve lived in Gaza.

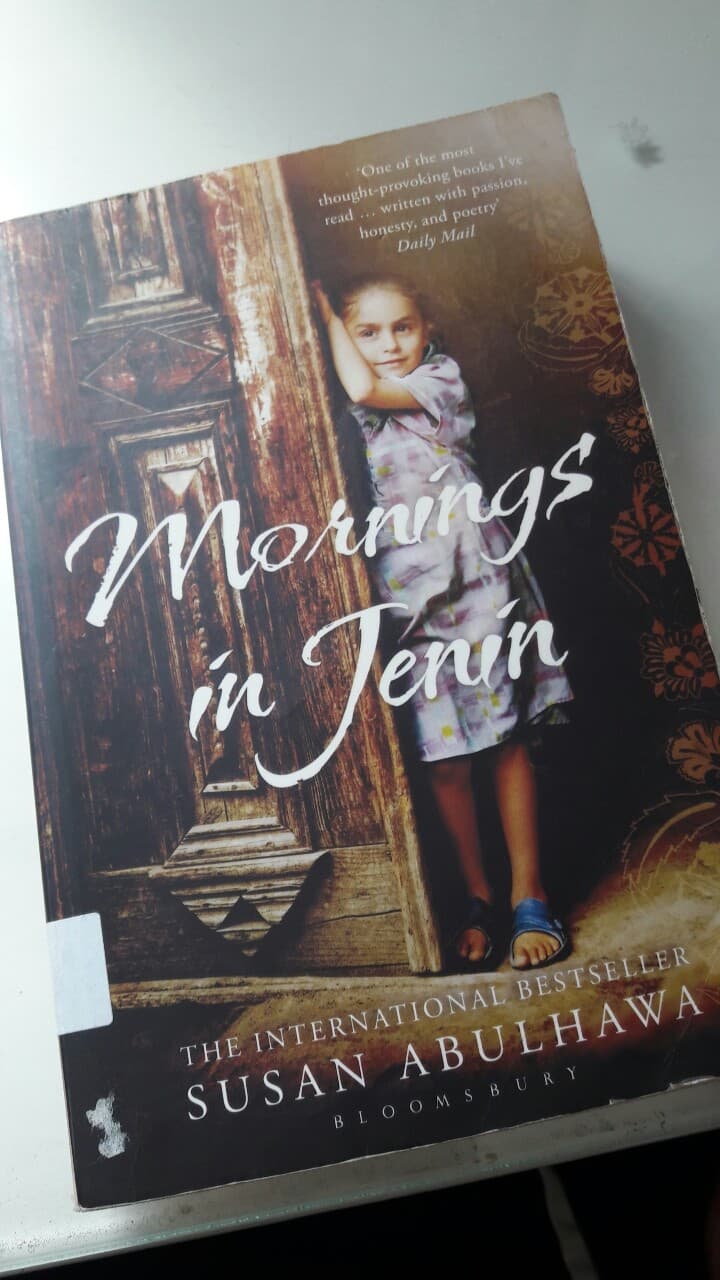

That memory and others crowded into my head as I read “Mornings in Jenin,” a novel by Palestinian-American author Susan Abulhawa. Her story made me nostalgic for historic Palestine—a land that is my ancestral home, and yet so unknown to me. All feeling of “belonging” has been robbed from me by the Israeli blockade of Gaza. Just like that girl with her raised eyebrow made me feel like some kind of alien, the government of Israel does the same to my people.

The heroine of “Mornings in Jenin” is a West Bank girl named Amal, who is given a scholarship to study for her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in the United States. Amal and I share the same dream, except she achieved it, I have not. Yet.

I see myself in Amal. However, even as I hope to travel to complete my master’s degree, I remember so many other Gazans who earned a coveted scholarship, only to see their dream vanish when they are not allowed to travel. Israel allows very few Palestinians to exit through its Erez gateway. The only other option is the Rafah crossing into Egypt, but that requires a lot of time, energy and money (in the form of bribes). If a miracle occurs and you’re able to cross, sometimes your visa for your ultimate destination is no longer valid, because it has taken so long to arrange.I am horrified at the thought of being one of those people whose hopes are raised so high, only to see them dashed because they cannot travel. Would the blockade on Gaza ever let me be Amal?

I am 21 years old, and yet instead of thinking about the topic of my degree, I imagine how I can overcome the obstacles to getting out of Gaza. This overthinking is killing me.

I force my attention back to the novel. When Amal meets the love of her life, the first question he asks is, “How was America?” In Gaza, if I ever meet the love of my life, he will most likely ask, “Were you in Gaza during the 2008 war?” This is how most people I meet for the first time start a conversation. They do not ask about my favorite book or what kind of music I am fond of or if I like “Al-daheeh” more than “Al-Saleet al-Ekhbari” (two programs shown on the AJ+ channel on YouTube). Instead, they want to know which wars I’ve survived.

What they are really wanting to find out is whether we have anything in common, since I did not grow up here. They want to share their memories of the war (how many relatives died, if their neighbor’s house was bombed and the fact that they were scared to death). But I don’t enjoy this topic. I also hate it when someone asks me, “What brought you here?” or “Which do you like most, Saudi Arabia or Gaza?” War is not the center of my memories as it is for most Gazans. I grew up amidst gardens, amusement parks, malls and corniches. I travelled around the kingdom from east to west by bus, airplane and train. It is not war that is the hardest for me to bear, it is recalling all of those sights and experiences that I cannot have in Gaza! For eight years I have wished someone would ask me about my favorite color, so I could answer with sparkling eyes, “orange!”

At some point, I stopped mentioning I was born and raised outside of the Gaza Strip, so I could avoid the interrogation.

I returned to reading “Mornings in Jenin” and hushed the ghosts in my mind. Lying in bed with my right foot on my left knee so I could keep the book at eye level, I read how Amal’s sister-in-law tried to play matchmaker between Amal and a young man. I began imagining what Jenin would look like if Palestine was Israel-free, until a loud boom split the air. I panicked, thinking the Israelis were starting their usual party (Gazan slang for bombing), and the book fell onto my face. “YOU BASTARDS!” I “sang.” My dad rushed outside to investigate and came back after an hour, telling us that bullets had been fired to silence a fight in the neighborhood. I laughed, thinking that this one time, I owed the Israelis an apology. Then again…if it were not for them, loud sounds wouldn’t automatically frighten me.

I decided to put down my book and try to sleep. I could return to “Mornings in Jenin”…in the morning.