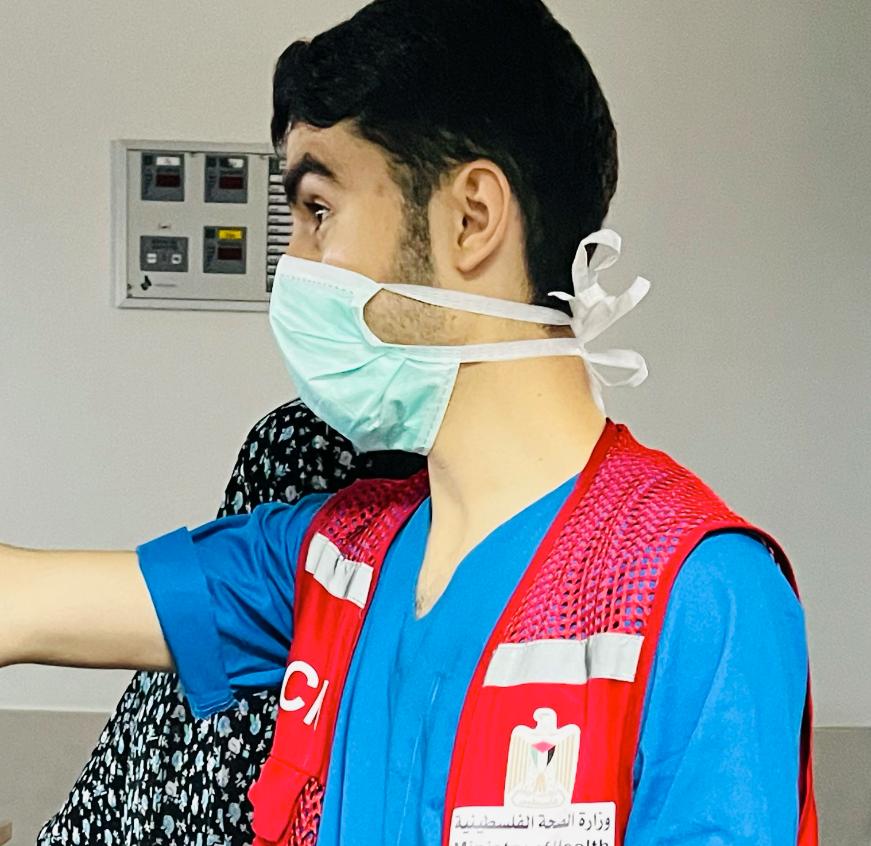

My name is Faress Arafat, 22. In September, I set out to achieve my dream of becoming a nurse, beginning my studies at the Islamic University of Gaza. Only a month later, life took a devastating turn, and I was forced to learn under fire. Everyone in Gaza has a story, and this is mine.

40+ days trapped in Al-Shifa Hospital

At the beginning of the war — or shall I call it genocide? — I was training as a nurse at Al-Shifa, the biggest hospital in Gaza. So, it was natural to keep going, helping people, especially kids, both medically and psychologically. I stayed at the hospital nonstop for over 40 days, surrounded by Israeli tanks. Meanwhile, displaced families – mostly from the eastern part of Gaza City — sought shelter in the courtyard, setting up fragile tents.

Those days are a blur. I focused only on my work, although I was also lonely, hungry, and traumatized. A few stories of the people I encountered stand out, however.

One time, I encountered a little girl, the sole survivor in her family. She was so in shock that she couldn’t tell us her name, and no one was there to care for her. She was bleeding from her head and needed an X-ray, but a queue of others awaited their turn.

When I was finally able to enter the exam room with her, the doctor asked, “What is this girl’s name?” My response: “Unknown 44.” He was puzzled, until he realized there were 43 others like her, nameless from shock and alone.

There is also the night when I was heading to grab a cup of coffee and heard the distant wailing of ambulances grew louder. A flood of wounded people arrived, with the paramedics carrying them on stretchers.

“What happened?” I asked frantically.

“They bombed the school where we were sheltering inside,” those who could talk told me. I joined the on-duty team, our hands moving with urgency as we tended to wounds, changed dressings, conducted examinations, and made referrals.

Suddenly, a father, along with his children drenched in blood, stood before me. “They bombed our house!” he croaked. “Check the kids first, and you can check me later, please!”

My hands steady, my heart aching, I stitched and cleaned the wounds of the children, then turned to the father. In the silence that followed, I whispered a prayer for forgiveness. I had allowed my faith to be eclipsed by the horrors before me.

You might wonder about the more mundane parts of my daily life during these days. Our usual meals were canned fava beans cooked over a makeshift fire made from cotton and alcohol! We often would go days with just one meal a day and some salty water. (Most of the water in Gaza is not potable, and this has particularly been true during the war.) Sometimes, we felt we were not hungry at all because of the horror that surrounded us.

Meanwhile, I could barely contact my family, who lived in our now-damaged house in the Al-Zaytoun area of northern Gaza City. My parents, three sisters, and two brothers were hosting other families at our house, and I was freaked out about something happening to them; according to the news, bombing was everywhere.

During the Israeli siege of the hospital, I couldn’t reach my family at all. For days that felt like years, I couldn’t hear their voices or even learn anything about them. Many crazy thoughts came to my mind, especially when I learned that Israeli tanks were in Al-Zaytoun and targeting our neighborhood.

I finally found out that they had evacuated from the north of Gaza to the south.

Evacuation

On November 18, we were allowed to evacuate the hospital with the help of the Red Cross. But it was a harrowing experience. Here is what happened to me and my colleagues:

Upon exiting the hospital’s main gate, I saw that the displaced people who had been camping outside were gone, although their tents and belongings were still there — just damaged and collapsed. It was my first time to see Israeli soldiers, tanks, and bulldozers, guns pointed right at us. To be honest, I was very scared.

We walked for dozens of miles on foot, with tanks and bulldozers surrounding us. Houses were destroyed. Cars were crashed and burnt. Decaying bodies littered the road. Trees were uprooted and burnt. The Gaza I knew no longer existed.

There were literally thousands of us trudging along, including patients, displaced people, doctors, and nurses. Many injured people who could not walk were pushed in wheelchairs. Dead cats were everywhere. I love cats, and I tried my best not to cry, but I did.

We came up to a small checkpoint, maybe 7 feet by 15 feet or so. We were ordered to cross one by one, but there were so many of us! Suddenly, everyone rushed forward at the same time. A small child fell under people’s feet. An old man fell too, and I tried to help him, but then I fell, too. I was forced to rescue myself and just run.

After the checkpoint, the soldiers called names of people they wanted to interrogate. I heaved a sigh of relief to not be among them. About two miles later, I hailed a donkey cart to take me to my family.

Reunion

I found my family was in Khan Yunis in southern Gaza. It was a huge relief to see them alive and in good health, but they had all lost weight and I could see horror and sorrow on their faces. And, oh my God, the house was crammed with people from different parts of Gaza.

I learned that my youngest sister, Asmaa, her husband and son were still in the north. They had never left, and my family had completely lost connection with them. Plus, my oldest sister, Samah, and her seven kids and husband were somewhere else in the south.

After a few days in Khan Yunis, we were told by the Israelis to evacuate to Rafah. We did not know anyone there, but we felt like we had no choice. In Rafah, we arrived at an area full of refugees in tents and decided to join them. Unfortunately, no NGOs or UN agencies provide tents, and my dad had to pay more than $500 to acquire the necessary materials. Luckily, we could afford it. But many others cannot! We bought wood and a plastic tarp, and my dad, who used to be a builder in Jerusalem and Gaza, used his skills to construct our tent. It broke my heart to see my skilled builder and engineer father work to replace the memories of our now-damaged home, abandoned at the war’s onset.

We also found a sewage well, so my dad built the tent atop it. That well serves as our toilet. Showers are out of the question. As for food, sometimes we must wait for long hours just to secure a few cans of fava beans and water. Other times, we return empty-handed. We don’t have enough blankets, mattresses, pillows, or spare clothes. Gravel and sand constitute our beds, so we must endure bone-chilling nights.

My dad also built a tent for my oldest sister, Samah, and her family, and now they are our neighbors. He also built one for my uncle and his entire family. Unfortunately, we still don’t know much about my sister Asmaa and her family, who are still somewhere in the north.

My new life

This is how we start our day: We wake up at 6 a.m. or even earlier to try to be the first ones in lines for food and drinkable water. Once we secure our lone meal for the day, we look for wood to start a fire to keep warm. It’s incredibly cold. If we are lucky and can have a fire, we usually make some tea or coffee and everyone gathers around.

When despair starts to overwhelm me, I escape for some alone time, which is almost impossible in the tent. I grab my laptop or notebook and journal. What distresses me the most, actually, is the lack of privacy. I have two sisters living in the same family tent, and I have no idea how they manage their hygiene routines, although we try to give them some private time.

We have been living in this tent for over a month now, and sometimes I don’t know how much longer we can handle it. This is simply not a life humans should have to endure. We deserve better.

Struggle and hope

To make myself useful, I volunteer as a nurse in the refugee camp. When I was forced to leave Al-Shifa and relocate to the south, I brought along some medical supplies and medications that I believed would be useful in camp conditions. With each passing day, more individuals arrive and set up new tents, using the minimal restroom facilities and resulting in the spread of more germs and viruses. I began spreading the word about my presence and offered myself as a resource.

Sometimes, I use my own money to purchase medications from nearby pharmacies. Usually, once the pharmacy owners learn it is for refugees, they provide the medicines for free. If I can’t find what’s needed, I travel long distances to the nearest hospitals, sometimes with accompanying patients. It’s mentally and physically draining, but this is my calling.