In 2011, after a long period of unemployment following graduation from college, I was about to begin my first professional assignment as an English translator. It was for a meeting about the crisis in the Sinai and it was being held at the Al-Mathaf, a hotel in Gaza. I was anxious but also happy to finally have an opportunity to gain experience in my chosen field.

I assumed I would be translating for a group of five meeting participants, or maybe ten maximum. But when I entered the hotel’s meeting hall, I was shocked—it was filled with many people of different nationalities and languages. I froze in place and looked around, vainly trying to spot a familiar face.

A man came toward me and said, “You’re Heba, right?”

Speechless with shock, I simply nodded my head. “Dr. Eyad recommended you and said that you are a qualified interpreter,” the man said. “Please sit here.” I did as he told me and sat down next to a British man, whose name completely slipped my mind as soon as he said it. The British man gave me an outline for the meeting. “Read this,” he said. “You can find all your answers here. We’ll be starting in five minutes.”

Is this man for real? I wondered, near tears. This outline is almost 15 pages! Where do I start?

I meet a great man

This panicky moment was the result of the workings of two great men. The first of them was my husband, Mosab, who has always supported me, even when I fell into despair because I had had no luck getting into a master’s program or finding professional work. The other great man was Dr. Eyad El-Sarraj. Mosab knew him because he was a relative through his father’s side.

One morning, Mosab called me and said, “I gave Dr. Eyad your C.V. He wants to meet you, so you have an appointment for 1 pm tomorrow.”

I was nervous, of course, because Dr. Eyad was a well-known politician, peace activist and psychologist. Working with him would add a lot to my career. But I worried that he would ask me questions that I wouldn’t be able to answer and then he would tell me, “Sorry, you're not a good fit.”

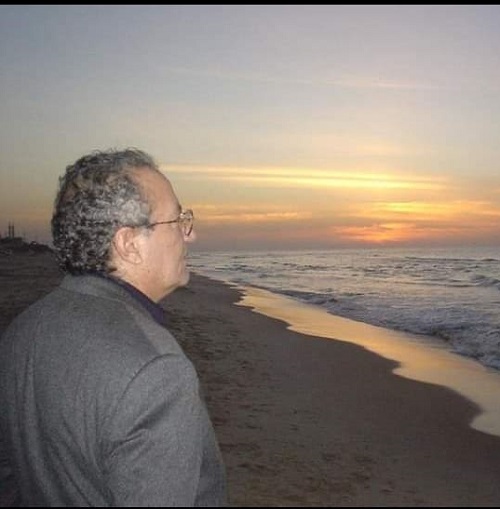

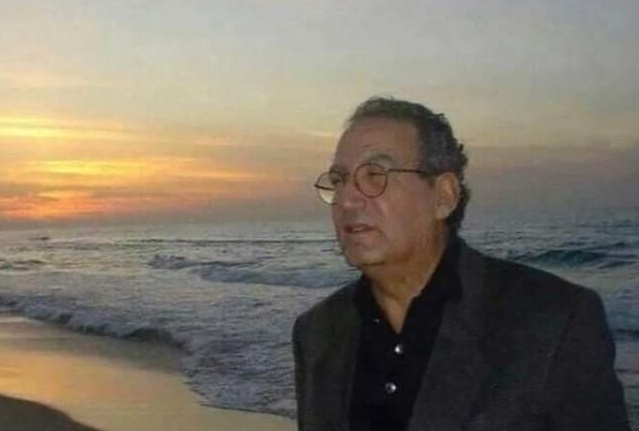

Mosab gave me courage by coming with me to the appointment, which took place in Dr. Eyad’s living room. To my surprise, he was wearing casual clothes and a pair of slippers. His house, however, was exquisitely furnished. A beautiful gramophone laid on the stool at the right side of the entrance. A large, well-organized library attracted my attention. My admiration for reading made me forget for a second the main reason for our visit. I wanted to go through every book in that library.

Once I sat down, all my fear faded away. “Your C.V. is very interesting,” Dr. Eyad said. “It’s not easy to find a fluent English speaker with a good background in project management. My assistant will contact you in a few days to assign you the first task. No worries. We’ll work together on your management background to empower you in your work.”

That was it! All the questions I assumed would be in the interview were not asked. Not only that, but he also praised me and reinforced me and my experience, and he wanted to enlarge on it, as if he saw something in me which I couldn’t yet see.

A storied career

Dr. Eyad studied medicine in Egypt in 1962, and he became more politically active starting in 1964 when he joined the Palestinian Liberation Front. After the defeat of 1967, Dr. Eyad felt frustrated, so he focused on his studies and stayed away from political affiliations. “I did not want to study medicine,” Dr. Eyad has said, “but it was my mother’s wish.” He graduated from medical school in 1971, the year that Israeli troops-occupied the Gaza Strip.

When Dr. Eyad came back to Gaza, he worked at Al Shefa’a hospital in the pediatrics and neurology departments. After one year working there, he went to Bethlehem Hospital to receive training in psychiatry. Then he travelled to the UK to study psychiatry. He came back to Gaza in 1978 and worked as a psychiatrist. At that time, psychiatric work was not accepted in Gazan culture, yet he defied all the obstacles.

Dr. Eyad founded the Gaza Community Mental Health Program in 1990 to help traumatized people, but his main focus was to provide psychological help for the children who suffered during the uprising of 1987 (the First Intifada). He believed that, without intervention, a generation who lived in a violent atmosphere will only produce more violence. And since every action has a reaction, where there’s hatred, violence or lack of justice, then the same is given back.

His main concern was to prevent the youth from living as victims and to defy the occupation by building up a generation that would never give up on their lands despite Israeli arrogance. As years went by, he managed to expand his small clinic and as well both his vision and mission. He helped women who lost their spouses, brothers and children. And he helped women who might face domestic violence yet wouldn’t talk about it, due to community restrictions.

Working with Dr. Eyad

When my interview with Dr. Eyad finished, I went home wondering, “What will my job be?” Only an hour later, Dr. Eyad’s assistant called to tell me about the meeting at the al-Mathaf Hotel, which Dr. Eyad would be attending. “Please be there at 6 p.m. sharp,” he said.

And that’s how I found myself in a room full of people speaking different languages and unsure of whether I would succeed or fail at my first assignment for Dr. Eyad. Fear controlled my mind, and I was about to cry. But then I closed my eyes for five seconds and mustered all my strength.

“I can do this,” I said to myself.

The meeting lasted almost two hours. I moved from one table to another, translating what was said. Translating an idea from an Egyptian or Palestinian journalist to an American or German journalist was not easy, due to differences in both culture and ideology. I had to use the proper words and sentences to convey my ideas. Yet whenever I felt lost, I took a deep breath and told myself, “You must nail this!”

And I did! I didn’t make any mistakes while translating, although I was exhausted by the end of the meeting. To my surprise all the participants thanked me and praised my efforts. I was over the moon and all my tiredness vanished.

The next day Dr. Eyad called me and said that everyone at the meeting was impressed with my translation. He asked me to translate some of his articles. Then I attended a meeting he had with a journalist to note down everything that he discussed.

Working part-time with Dr. Eyad was a good start to my career indeed. I applied for a two-month contract and got the job, and I received an excellent evaluation when my contract ended. Then I got another part-time job with a good salary. Through all this I continued working part-time as a translator with Dr. Eyad.

He left his imprint

Then days passed, and I didn’t receive any calls from Dr Eyad’s assistant. Later on, I learned that Dr. Eyad had left the Gaza Strip to get therapy because he had a relapse of leukemia, which he had contracted in 2006. I prayed that he would get better, but in December 2013, Dr. Eyad left this world, leaving behind a great legacy.

Dr. Eyad lit a light of hope inside every desperate person in Gaza. He dreamed of a better future for Palestine and the people here. For me personally, he gave hope at a time when I had nearly none. I know everyone has a different view of him, nevertheless, he left his imprint. Whenever Dr. Eyad’s name is mentioned, the Palestinian struggle for justice comes to mind. May his soul rest in peace.