On August 25, I had an interview for my dream job—teaching English for UNRWA, the U.N. Agency for refugees. I studied very hard for that interview; for almost a month, I stayed away from all social media sites, since I consider them time wasters! I only opened Facebook for five minutes a day to see updates from We Are Not Numbers and to check for important communications on Messenger.

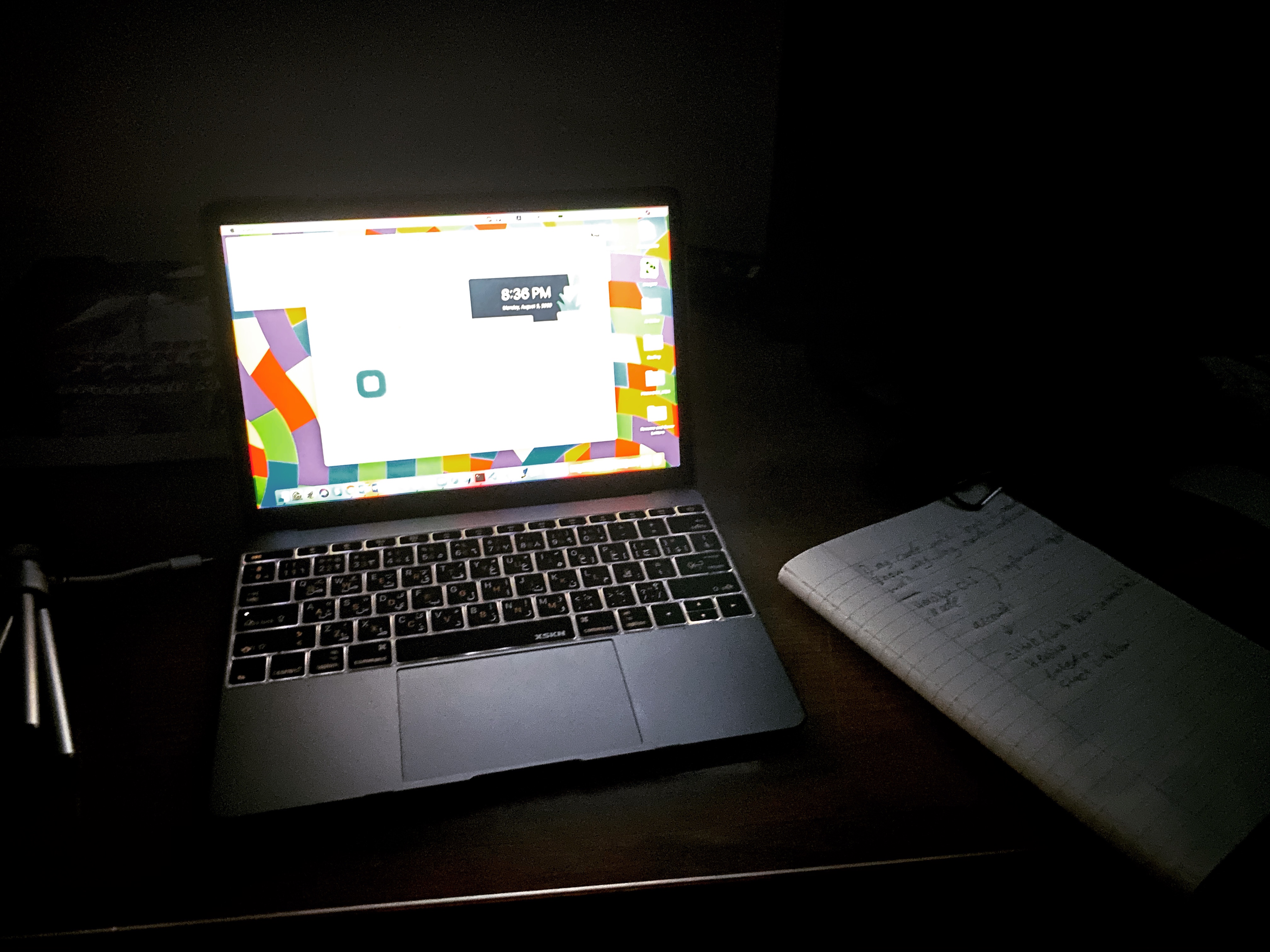

The night before the interview, I slept at 10 p.m. and awoke at 1 a.m. to continue preparing. The electricity was out; my fan had run out of battery on that very hot night and all of my family members in our ‘dark’ home were sleeping. I made a cup of Nescafé, prayed two Rakaat (Islamic prayers), turned on my mobile phone flashlight and started studying in our large living room. As usual, I was alone, with the small beam of light on my notebook in the middle of the darkness. The only sound was the voice of crickets wafting through our window.

I don’t know why it suddenly occurred to me at 4:20 that I could take a look at Facebook using an internet card bought by my brother. The connection wasn’t good, but I wanted to check for any tips related to my interview, since there is a group on Messenger for that specific purpose. I clicked online and I really wish I had not! Everyone was anxious talking about the latest news: four people deep inside the Gaza Strip had tested positive for the coronavirus we had feared for so long. (I truly thought we had escaped it; “thanks” to the tight blockade under which we live.)

I literally did not believe what I was reading until I received a message from UNRWA saying all interviews, including mine, had been cancelled. I felt very badly at first. But then I felt drawn to learn more about how the coronavirus had made into Gaza, and I soon forgot about my own troubles.

I read the story of Heba Abu Nadi, a Gazan who travelled through the Erez Crossing to Jerusalem with her sick young daughter, who needed surgery at the city’s El-Makassed Hospital. At first, Israeli authorities refused permission for her to pass through the Erez checkpoint, so she returned home after spending four hours trying to accompany her daughter. Could you imagine how desperate she felt? The next day, however, she tried again and was allowed out this time. She was later tested for COVID-19—and learned she had the coronavirus.

This poor woman is all over the social media sites. Some people say bad things about her for infecting her family members and thus putting all of Gaza at risk. Others pray for her. Still others make jokes! As for me, I put myself in her shoes. How is her sick daughter now? How does Heba feel, with everyone blaming her for the disastrous situation in Gaza? Or, is it all an Israeli plot to destroy Gaza and she is just a victim?

Oh, Gazans! Please stop blaming that poor mother! We don’t know the real truth. She must be miserable, worrying about her daughter and perhaps being responsible for infecting four members of her family. Even before this latest catastrophe, life had become so much worse in Gaza. We are getting only four hours of electricity a day, and now we are all quarantined, adding insult to injury.

One Facebook post was like adding much salt to a blood-shedding wound: A girl outside Gaza said COVID-19 is common now and is nothing to be so panicky about. But Gaza is not like any other place! Gaza, this tiny spot on the map with 2 million people has only one main hospital, where more infected people were recently found, forcing the evacuation of an entire department. Do you know our doctors risk their lives for monthly pay of only $300 a month? Yes, my readers, $300, not $3,000. And thousands of others are receiving no salaries at all right now.

On that first day, my father told my little brother Hamza to go out and buy drinking water, because we had run out. (The water from the tap is not safe.) But after that, my father said, Hamza should stay inside, refusing to leave even if he himself asked again. Realizing this was our last chance, we all wrote a long list of other items we needed, like snacks, from the only open supermarket in our area. Hamza only saw police officers in the streets, who were stationed there to prevent non-emergency trips.

Meanwhile, my father kept his tiny mobile radio on, tracking the COVID news. My sister Walaa’, a Tawjihi student, keeps studying for her final exams, but feels afraid of the coming days. She is confused about whether to study, sit with us or talk to her friends about how they had spent their day. However, my younger siblings are delighted that school is closed. They are still too young to understand what the curfew is all about. As for my mother, she makes manakish (our version of pizza, topped with thyme and olive oil). She always makes it during wars and other emergencies. (And I bet she is not alone; every house has tons of thyme and manakish is inexpensive to make in large quantities.) The two have become synonymous.

I suddenly remember the winning essay I wrote for the We Are Not Number COVID-19 writing contest. In that piece, I claim that Gaza has proven itself to be the safest place on earth when it comes to the pandemic. When I wrote it, I morbidly thought the horrific Israeli blockade of Gaza, which prevents most travel in and out, would for once keep us “safe” while others suffered. My essay was about to be published, but does it deserve to be now? And if so, will it be read? Or will I be laughed at or ridiculed like poor Heba?

In any case, I will rely on my belief that these miserable days will end—not because of hope, but rather my magical faith in our Lord and that everything He “writes” is for our sake, no matter how miserable it first seems!