It was night and my 7-year-old daughter, Asmaa, and I were bored, sitting in our small garden on the swing. “I would like to say something, but I wish it will not happen, insha’Allah,” she suddenly said.

“It’s OK. I’m listening,” I replied.

“Mama! If the Israelis target us, I hope they do it at night when I’m sleeping. Because I don’t want to feel the pain of death,” she said.

I couldn’t reply for few seconds. I have the same wish, too.

“Don’t think like that,” I finally said as I stroked her hair. “These bad days will pass and we will enjoy a better time.”

A different kind of war

The Israeli war against Gaza has been going on for three months now. At first, we thought it would end after a few days, then we would return to our daily lives. But it soon became clear that this war is totally different. Israel is not only targeting freedom fighters and their institutions; it is hitting random places and people. And it’s not destroying “only” an apartment or building; it is bombing entire neighborhoods. That was not the case in previous wars. There is no safe place, so we stay at home and adjust to the absence of electricity, gas, and water.

We charge our phones and batteries (for lights) by bringing them to our neighbor or the local mosque, where there is solar power. When that’s not possible, we’re cut off. And even when our devices are charged, there are long blackouts, without even access to a phone signal so we can read the news on Telegram. As for water, it comes only every eight days for three hours, so we must collect as much as possible in cans.

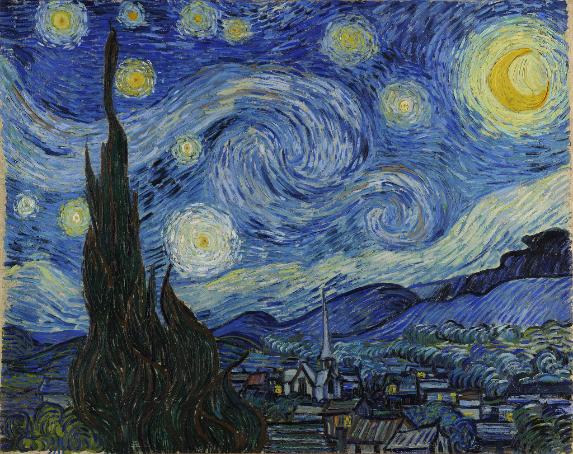

The Israeli bombs increase at night, so we go to sleep early, hoping to lose ourselves in oblivion. The other day, I had barely fallen asleep when I heard a massive bomb. How to describe it to someone who hasn’t lived through a war? It’s rather like the loudest thunder you have ever heard. It makes your bones vibrate and your heart beat very fast. Everyone gathered in the living room. Outside, there was no light in the street except from the targeted house, which was now engulfed in flames. After about 30 minutes, firemen and an ambulance came. But no one inside appeared to be alive. Of course, after that, it wasn’t easy to fall asleep. Nevertheless, we managed.

War has forged a ‘new normal’

We woke up before sunrise, feeling grateful to be alive and together. Then the hard work started. At the beginning of the war, when we no longer could get fuel, we built a wood-burning oven. Now, the men chop wood every morning, so the women can prepare a fire and bake bread — a long process for so many people. As soon as I’m done, it’s time to prepare lunch. Meanwhile, the drones and fighter jets roam over our heads, and we’re terrified that the smoke of our fire will attract them.

While I was busy preparing food, my 10-year-old son went with his cousin to the mosque to pray for our martyred people before they are buried. When he came home, he told me in awe of seeing one man whose body was almost totally covered by a blanket. But one of his hands stuck out, and his finger was pointing up. In a prayer before dying, Muslims say Ashhadu an la ilaha illa Allah (I bear witness that there is none worthy of worship but Allah). Then we extend one index finger to mirror the prayer. If a person doesn’t have the strength to use his voice, sometimes the finger is the only way of “praying” that is possible.

Not too long ago, my children were too scared to go past the door of our home. But as the weeks have droned on, they have started to go to the garden, the street, and now even the mosque. And they’re shopping again, too. The increased demand has made everything more expensive and there are fewer and fewer items on the shelves.

“I wish to eat biscuits with tea,” my son said, about to cry.

“There is nothing we can do. Feel grateful that we are still in our home and have something to eat,” I replied.

But to be honest, we all miss food we used to take for granted. My daughter wants chicken. And I miss eating dark chocolate and drinking coffee while writing this story.

A new presence: the specter of death

The number of people living in our town of Rafah increases every day, as more people crowd into the south to escape the Israelis. Every day there are lost children in our neighborhood, looking for their families.

Suddenly, a fighter jet flies fast and low over our house, making the children run home, shouting and crying.

“When I hear the sound of bombs or fighter jets, I start saying the Alshahada,” my son Mahmoud admits to me.

“Me too,” I said.

Death could come at any time; I believe in this, and that Allah’s mercy is bigger than anything. After death, we will go to heaven, inshaalah, and I will be with my mother, who died of COVID without me by her side. But I don’t want it to come without any warning, and the opportunity to say goodbye to those I leave behind.

Meanwhile, however, there is no sign that this war will end soon, and it feels increasingly likely that at one point we will be forced to leave our home like so many others. Every one of us has prepared a small bag so we are ready for such a miserable development.

Now it is night once more and we sit on our balcony, making tea on the fire and listening to the radio. I enter the house to bring back a cup of tea to my son. While I was in the kitchen, another massive bomb hit. The windows shattered, and I froze in my place for few seconds, terrified of going back outside and finding my family to be only dead bodies.

Thank Allah, they were sitting as if they too were still frozen in place. I took a long breath, trying to shake off my shock. Then we all went outside to see where the rocket from the drone had hit. The target was the house behind us — our neighbors, who were civilians, not military members. An ambulance had begun to take the injured away. My son shouted, “There’s a man full of blood!”

At least we are together

My sisters-in-law recently moved into our house as well; the home of one was destroyed and the house of the other is in danger. “We couldn’t sleep, day or night; the bombing never stopped,” one of their children explained upon arrival. “I saw people dead and blood everywhere.” We are now 17 persons in one house in Rafah, with no income among us. When a rare truck with food and other aid appears in the street, the children clap and shout.

Days later, drones and fighter jets appeared once again, making a high, piercing, whining noise. Suddenly dust, sand, and smoke filled the air. Household items flew through the air. We shouted each other’s names. I couldn’t breathe because of the smoke, but I managed to shout anyway: “My children!” Fortunately, everyone was ok, except for one of my sister-in-laws, who was bleeding along with her son. An ambulance was able to get through and took them to the small hospital in Rafah.

We learned later that the building next door, the same one that had been damaged earlier, had been destroyed, with over 40 people killed. One of them was my friend Hibba, who died along with her mother and children. Hibba and her mother had visited us many times. Hibba’s husband was at the mosque when the Israelis targeted their building; he went mad when he returned and found his family gone.

Now, we don’t think about the future. Death is closer every day. Nowhere is safe. We are grateful to live just this moment.

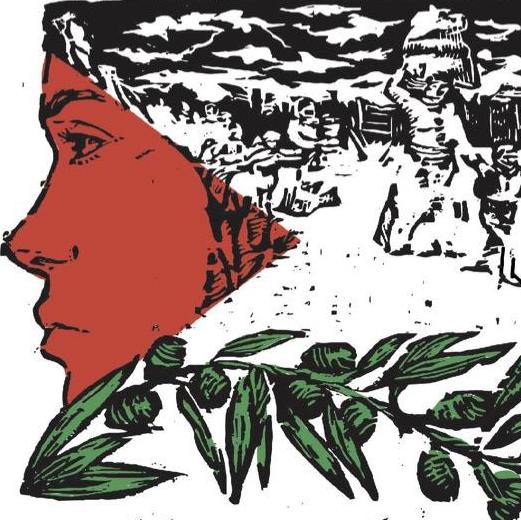

I was afraid to write this story at the beginning of the war. Israeli occupation soldiers target journalists and social activists, including writers in WANN, such as Mahmoud Alnaouq. But then I decided to write anyway, because we aren’t safe no matter what we do. And by writing this story, I hope more people in the world will understand who we are and the life we live and support the call for a ceasefire and an independent Palestine.