Dearest Mum and Dad,

Do you remember the moment when I informed you, at the age of 18, about the scholarship I had gotten to pursue my studies abroad? Well, maybe you don’t remember it in detail, because I kept so much inside. But I’m ready to share it all now.

I’m sure you remember my trip to attend an international youth conference in Paris. Let me start there, and tell you more about that trip. At that time, I was very eager to know what it looked like outside the open-air prison I had lived in since I was born. I wanted to know what freedom looked and “lived” like. I was curious to know about each country’s culture, traditions, language and so on. I knew it would be different, but assumed everything would look normal to me. When I went to France, though, nothing seemed normal. I was amazed that one of my dreams had actually come true! We Palestinians learn that dreams usually stay just that—dreams. I felt like an alien among the youths from Europe and Africa. Despite this, I worked to become close to all of these people.

Leaving Gaza

When the time to return to the Gaza Strip came, I had discovered a small part of my personality that was new. I built bigger dreams. I imagined a different life, with people from various backgrounds. All of these things encouraged me to start looking for a scholarship abroad. I found it and went all through its procedures without informing anyone. I only shared it with you the moment I learned about winning it. I remember very well, as if it happened just minutes ago, how I shouted in a voice very loud from happiness. But I also still remember how you, mum, started begging me not to leave Gaza, with your tears running down your beautiful face. Dad, you woke up, shocked by my shouts, and asked me what was going on. You didn’t react or comment, but I could see the sadness in your eyes. It was because I would be leaving you. I was selfish; I hadn’t even thought about your feelings or worries.

Then I had to leave the place where I spent 18 years of my life, seeking to fulfill my hopes. I arrived in Turkey to begin making my dreams come true, expand my experience and learn more about this big world. The Turkish language looked so weird to me. I thought I would never manage to speak it. Everything else seemed different and harder than what I had expected as well—even little things, like the toilets. “Squat toilets” are still in use at the dormitory I lived in for almost two years. I didn’t know how to use them! I will never forget when I fell down on the toilet; I smile whenever I look at the scar that remains on my hand.

Trying to adapt

Perhaps the hardest aspect of my new life was getting used to the “sexual culture” among youth my age. I cannot deny that it felt fabulous and weird at the same time to enjoy the freedom of dressing in the way I had always wanted without the restrictions of the patriarchal and conservative society of Gaza. But it also caused problems. In Turkey, people can understand from a glance what someone of the other gender wants to communicate. So many behaviors relate to sex in some way. For example, if you look at someone in school, it means you want a physical relationship. I had no clue about that, coming from a place where sex has always been a red line that my gender is not allowed to cross. I was a naïve and ignorant young girl when it came to relationships, and faced much harassment. I took to carrying pepper spray around with me!

I was shocked by the fact that I didn’t feel prepared enough to live by myself, far away from my parents. I thought being raised in an open-minded and motivating family would have prevent the disorienting sense of cultural shock. I realized later I should have known that living in the open-air prison that is Gaza had played a bigger role than I realized. I spent my first two weeks crying and calling my parents via Skype. Mum, I remember how you refused to talk to me because your emotions overwhelmed you. It took me more than six months to adjust to the new lifestyle, but you still haven’t gotten used to the fact that the blockade now has robbed you of four of your children. I was only the first of us decide to leave Gaza to achieve my dream of living independently. I soon was followed by Majd, Majed and Shahd—and now we are all in different countries! I know you understood that seeing us again and witnessing our changes in adulthood would not be possible very easily.

Still a child inside

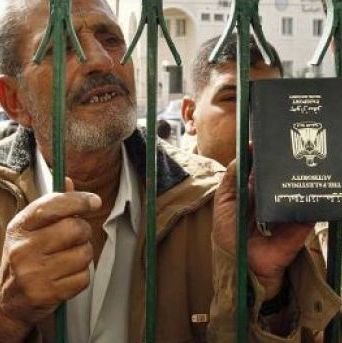

Four years have passed, and I still cannot believe all of the changes in our lives. I even tell curious people I have been here in Turkey only eight months. I left Gaza a dreamer and a “child,” but today I am working with many organizations to help refugees and in a few months, I will graduate from university. I’ve been able to travel a lot domestically and internationally, but I’ve only able to see you once during all of these years due to the closure of the borders by the Israeli occupation and Egyptian authorities. I remember that one time. I couldn’t handle being away any longer, so I decided to return after a year. You repeatedly said, “We miss you, but we don’t want you to come back!” I only understood why you said that after I was in and tried to leave again. I spent more time at Rafah border with Egypt, trying to exit before I missed the deadline for resuming my schooling, than with you. I spent almost a full month going daily basis to the border in the south of Gaza. When my name was finally put on the list of departures, I left home without even a farewell hug. I had hugged you every single day for at least a month, and I had given up; there was no need hug that day, I felt, because I was sure my name would not be called. I miss that lost hug.

After these years of separation, I am more mature than before, but on the inside I am still a child who misses her parents’ warm-heartedness and love every day. Only a few months separate me from my graduation ceremony. You will not be able to be next to me on that special day, but your spiritual presence will surround me as always. I know I will envy my friends whose families are by their side. In normal circumstances, graduates have post-university projects and plans lined up. But plans are difficult when you are a Palestinian from Gaza. I wish I could tell you that I want to visit you for a while and then travel to Europe to pursue my master studies. However, my future is unknown and linked to the political developments in the region, as well as to who will offer a visa to a Palestinian from Gaza.

I am so thankful for you and for all the ups and downs that shaped my character. But I wish I could return back to Gaza to hug each of you and try my best to do something there to help my people.

Your beloved daughter,

Tamam