Our whole life we have fought with the world to be recognized. When we were asked, “Where are you from?” and we respond with “Palestine,” we would often be mixed up with “Pakistan.”

Now, the whole world knows us, but what a high price we had to pay just to be recognized.

A line by Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish goes, “And if they give us back the places, who will give us back the comrades?” Neither the places nor the comrades exist anymore. The places are demolished, and the comrades have been killed.

I have been struggling to find proper words to convey the indescribable, horror-filled reality in which I now live. Every time I open my laptop to begin writing, I find myself watching memories from home, from my old life, and crying, because I can’t fathom the idea that what is left of my entire life is only memories.

I have always felt profoundly rooted in Gaza. It is the ground of my very being — I never imagined living anywhere else. Whenever I talked with my friends about leaving Gaza, I would say, “Even if I travel, I know it is going to be a temporary thing. Gaza is always going to be the last stop. I cannot imagine life anywhere else.”

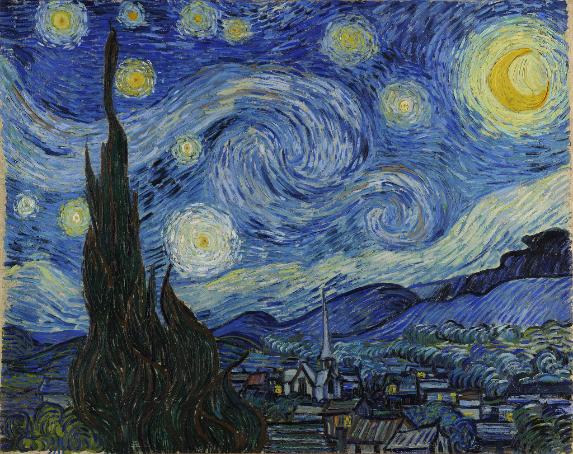

Prior to Oct. 7, even if life was hard here, it was still worth living. We Gazans managed to create a beautiful, culturally rich, and prosperous city filled with life, happiness, and love despite the ever-present blockade and the frequent aggressions on Gaza.

International law, which I loved and studied, failed us

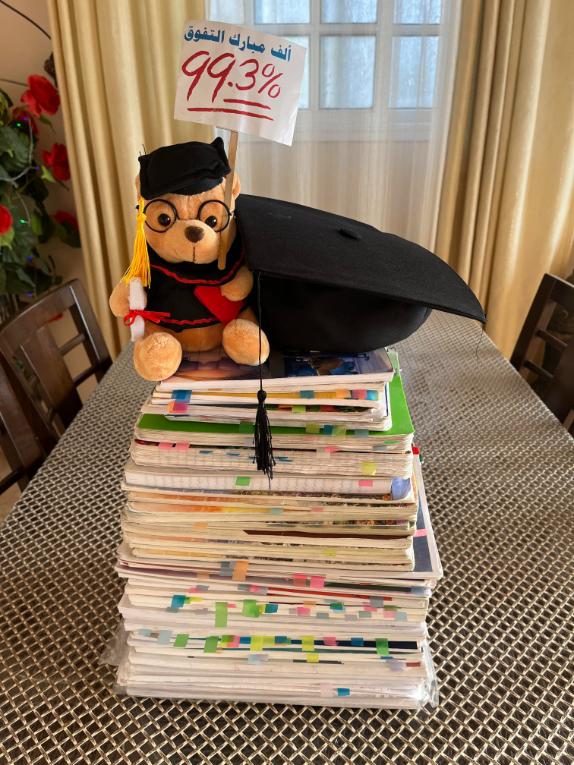

After graduating from high school in 2020, most of my friends traveled to study abroad but I chose to remain in Gaza and study law, my dream major. I was intrigued by international law the most. I dreamt of seeing myself in international forums, representing and fighting for my country.

Little did I know there would come a day when what I studied would fail me.

Not only did it fail me, it failed 2.3 million other Gazans as well.

International law declares that treaties are obligatory to its parties and international customs are obligation erga omnes (obligatory to all states). Rules that govern the conduct in armed conflicts, known as international humanitarian law (IHL) — represented in the Geneva Conventions and Hague regulations — are considered erga omnes. However, Israel does not seem to care for them, as no international legal consequences have been taken in the face of its aggression.

During a course I lectured as a peer tutor with the Al Mezan Center for Human Rights, I offered a session about IHL, which mandates, among other things, that it is forbidden to attack civilians during armed conflicts. In that session, fellow peer Wael Besaiso caught my attention. He was very attentive, listened carefully, and was interested in knowing more.

During the ongoing genocide, Wael along with his family was massacred when Israeli bombs targeted his grandparents’ house, killing over 40 people at once.

I wish I could apologize to Wael, because the IHL failed to protect him; because the whole world failed him.

I also wish I could apologize to my dear friend, Mohammed Zaher Hamo, because he too was failed by the world.

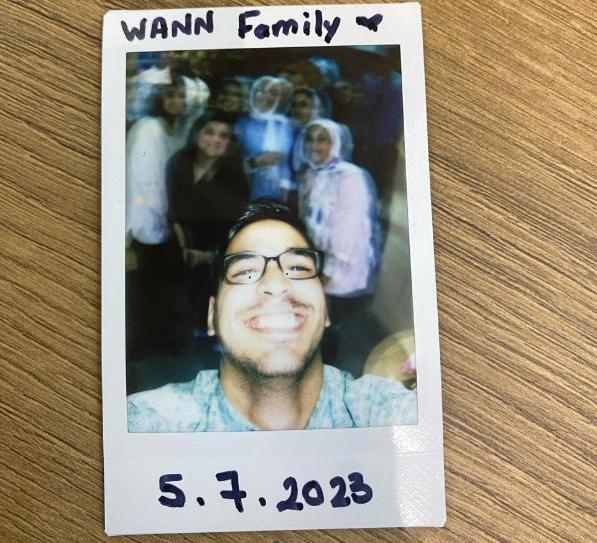

I met Mohammed through WANN. He had the kindest heart, always wore the brightest smile, and had an amazing capacity to befriend everyone. He was like the father of our group, always bringing us all together, encouraging and advising each one of us to write new stories, and coming up with new ideas to make our cohort the best.

When Mohammed and his family refused to leave the north, I was extremely worried that something would happen to them. At the same time, he was afraid that something might happen to those of us who evacuated to the so-called safe areas in the south of Gaza.

When I evacuated Gaza City to take shelter in the south, we regularly checked up on each other, so when Mohammed disappeared for two days, I was worried that something might have happened to him.

The night before the temporary truce started, I got the news that Israeli warplanes had murdered Mohammed and his family in a horrendous massacre that took the lives of more than 100 people.

There were to be no more messages from Mohammed, no more jokes, and no more being blessed by receiving his point of view and commentary about my writings.

I was lucky to know ambitious people like Wael and Mohammed, with big dreams and high hopes.

Wael, Mohammed, and the 30,000+ martyrs are not mere numbers. Each one of them possesses a story of strength and hope that was cut short by the Israeli missiles, tanks, and gunboats.

Now that our places are demolished and our comrades, as Darwish calls them, are gone, we are left with our lives in fragments, dispersed across the war-torn landscape of Gaza.

Our traumas are trivial, compared to their deaths

Amid the overwhelming and ongoing atrocities, we don’t talk about the small battles and traumatic experiences we face daily, because they seem trivial compared to these huge events.

How can we talk about not being able to shower for 10+ days to preserve the scarce amount of polluted water we have (not to mention the scarce food, medicine, and medical supplies), when at least we are alive?

How can we talk about not having the luxury of catching a cold since there is no medicine, when others are having amputation surgeries without anesthesia?

How can I talk about how much I miss sleeping in my bed, when so many people are sleeping in tents or on the streets?

How can I talk about missing the taste of coffee or complain about only eating canned beans and feta cheese when my best friend, Fatma, in the north of Gaza, is facing forced starvation?

How can I talk about the harsh smell of the phosphorus bombs when others are getting burned and deformed by them?

It feels ridiculous to worry about my senior year, my university getting annihilated by the Israeli missiles, the demolition of every Gazan student’s academic future, or the future in general, since the genocide hasn’t stopped yet. After all, we don’t know if there will be a future or not…

Survival’s guilt is not just the prerogative of those who have survived the genocide and were able to leave Gaza. Many of us feel guilty despite still being under the bombardment.

Enough misery to fuel a lifetime of creativity

I used to wonder if creativity only comes from misery. I always asked myself, “What would happen if Palestinians were no longer miserable. Would we still be creative?” I now believe that we would, because the misery we have suffered, and are continuing to suffer, for the past five months will forever be engraved in our brains. And no matter how much we write and talk about it, it will never be enough.

The international support we see — the rallies, the protests, and the boycotting — are what is keeping us hopeful. It is the thread of hope we hang on to: the belief that humanity is not lost, that there are people around the world who feel our pain and are standing up for us.

Hopefully, the continuous pressure on the international community and decision makers will be able to stop the illegal genocide.

Inshallah, there will come a day when Gaza will be free, when in fact all of Palestine will be free. Where we no longer live under a blockade, when there will be no genocide, when we will live happily and in prosperity so that the lives and places we have lost will not have been lost in vain.