As an English trainer at a private school in Gaza, I always try to improve my teaching methods. After five months of following the usual practice of asking my first-level (beginner) students to write basic sentences, I decided to try a change. I ask the students (who start at age 15) to write a story. I thought it would be wonderful – but instead I got more than I bargained for.

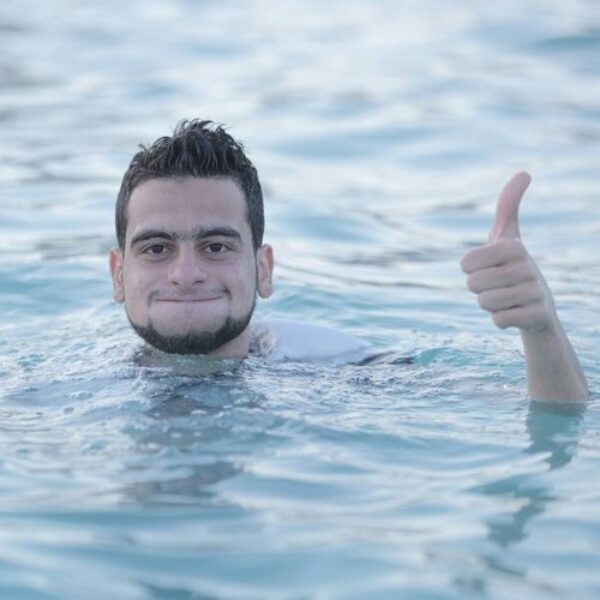

At the next meeting, I asked my students to write a short paragraph about any topic they liked. When they returned for the next class, they were full of stories they wanted to share. Then it was the turn of a calm, introverted, shy 20-year-old. He stood up, just next to his chair, and started reading his story from an untidily written sheet. I listened carefully as usual to give feedback, but this time my heart was the listening organ.

“I want to talk about my family,” he started. He went on to describe his family’s experience during the Israeli aggression of 2014, in broken English I could hardly decipher. The last lines, however, were short and clear: The young man said in his low, hesitant tone, “My mother, sister and uncle were killed, our house was destroyed, and my father and I were injured.”

I was shocked, and my heart hurt. My eyes were full of tears, but I had to hold them back. I had to, to stay in control. My pain deepend when he concluded with, “I’m sorry to tell you this story, but I have nothing else to talk about.” He sat down.

I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t know what to say. I found myself blabbering, “Good presentation. May they rest in peace.” I should have hugged him. Oh God, I should have hugged him! I wanted to kill myself for reminding him of their deaths!

The next day, I started my other class by sharing what had happened the previous day. I told them what the young man had said, how I felt and what I should have done. Unexpectedly, I saw tears fill the eyes of an 18-year-old girl. I instantly smiled and said in a rush, “It is fine. No problem. Everything will be fine,” even though I didn’t know what was wrong. A youth next to me whispered, “Her father was killed by Israel last summer.”

I wished I had never become an English teacher. I had broken two hearts in two days. How heartless I am! How reckless I am! How encumbered with sorrow I became and I still am.

The memory became like a stain in a notebook of my worst moments. Yet life goes on.

Two or three weeks later, the new lesson was “What’s your job?” and the class was easy-going. As everyone knows, teaching English requires explaining the different subject pronouns and the subject-verb agreement rules. I clarified, “We say, ‘I am a teacher, a student, etc.’ when we talk about ourselves. What if we want to talk about someone else?”

Answers were thrown out and everyone finally seemed to understand the rule. “Now let’s practice,” I encouraged. Everyone was supposed to tell me a sentence about someone else in the class. Finally, it was the 18-year-old’s turn. She said, “My father is a teacher.”

I had to ask myself if education professors have found a way for teaching the past simple to talk about murdered parents.

Mentor: Rachel McCrum

Posted March 27, 2016