On the first of January, 2024, while individuals around the world celebrated the New Year, Gazans were expressing gratitude toward God that we were still alive after after 88 days of aggression without letup and long days of devastating massacres.

I am living through the sixth or seventh assault in my lifetime. There have been so many I have stopped counting. In any case this last one is totally distinctive. It is the most furious assault I have so far survived, and hope I continue to survive.

In the second week of the assault, I left my house and have not seen it again. I have no idea if it has been destroyed or not, because there is no reporting coming out of my old domestic zone, which has been taken over by Israeli forces. The press is not permitted to enter areas where Israeli tanks have invaded, and they would have no security if they went in anyway. In this situation I finally realized the meaning of the old saying, Home Sweet Home.

Two weeks later, since I am in my final year as a medical student, I began volunteering as a doctor at the Nasser Medical Complex. I saw hundreds of crisis cases. One day I suddenly met my old classmate Lina, who was staying in the hospital as a casualty of the war. Her house had been crushed with the family inside. She was admitted to Al-Shifa Hospital in Gaza with multiple wounds, including temporary memory loss, which she regained after two weeks. Her major injury was to her spinal cord, which made walking difficult.

One of the patients I dealt with, Reema, is only 10 years old, but her childhood innocence was stolen by fire. She was in her house while she was sleeping quietly. Suddenly, she was facing flames due to a bombing in their neighbor’s house. The first time I was scared by the burnt flesh and angry red welts. Every time I see her for a follow-up appointment, she asks the same question: “When will my face be normal?” It echoes unanswered in my own mind.

I wish I could offer a picture of the future, but the mirror refuses to be kind. Each visit, it’s the same dance of hope and harsh truth.

Another patient I dealt with was Emad, a married man in his thirties. He was the caring father of two innocent daughters. Once a titan of construction, he was now confined to the sterile white walls of the hospital. His house was bombed, collapsing on him. This had left its mark not just on his body — a mangled symphony of broken bones and shattered dreams — but on his spirit.

Hemiparalysis (one-sided muscle weakness), a cruel twist of fate, had chained him to a wheelchair, silencing the once booming laughter that filled his home. His mind, a constant battleground, fought between the fierce love for his family and the suffocating fear of the future. Would he, the provider, the rock, become a burden?

The assault taught me the meaning of suddenly having to say farewell to loved ones. During the attack my family and I moved with my uncle to an apartment that was supposed to be safe. My uncle had a daughter Tala. We played cards daily during the attack to relieve our stress. One day I told Tala that after the attack I would miss her, since we would no longer be living together. One month later Tala was admitted to intensive care due to poisoning from the phosphorus that was used by the Israeli army. As a result of this poisoning, Tala died. I never expected that, and I will miss her forever.

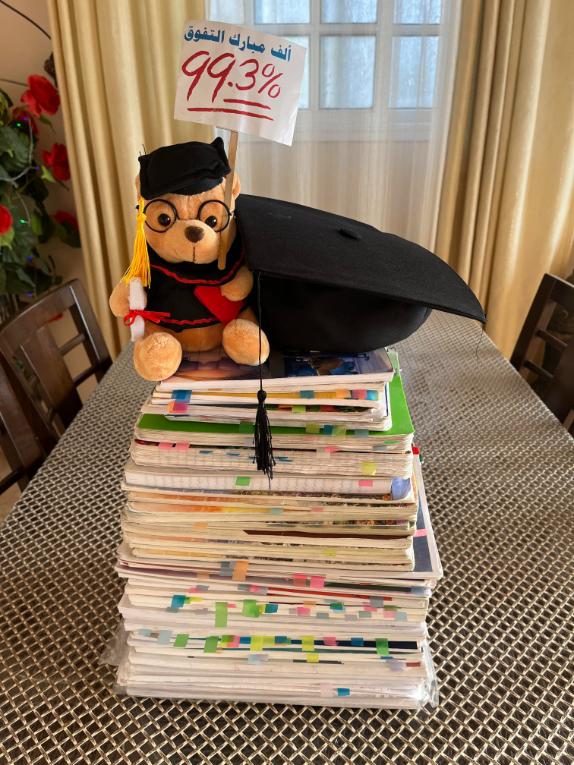

This attack has been devastating and impacted all major aspects of my life. I miss my house and cannot wait until the moment I can see it again. I lost my university that was destroyed by the Israeli attacks. I lost my dream, as I was supposed to graduate this year to officially be a doctor. My colleagues and I were preparing for graduation but Israel has made it impossible. I lost family members who were close to me.

I currently have only one dream: to put an end to these massacres and allow Palestinians to live without facing the fear of being bombed every day.