It was Thursday, March 19, three days after universities in Turkey shut down as cases of COVID-19 began to accelerate around the country. Normally, I love wandering around Istanbul, this time was different. The novel coronavirus had invaded, and the anxiety was palpable.

Just those three days at home without seeing the street had driven me a little crazy. “It isn’t that dangerous outside,” I reasoned to myself. “I’ll make sure to keep my hands in my pockets and not touch anything.”

I went to all of the most popular places (Taksim, Eminunu, Sultan Ahmet and Fatih), yet I found a frighteningly different Istanbul. The usually crowded streets contained few people, all walking alone, trying to keep a safe distance from each other. Looking at their faces, their eyes filled with caution and anxiety, reminded me of my family, with similar cautious and anxious looks, evacuating our house by the border in Gaza during regular Israeli invasions under the hovering drones.

Standing on the deserted Galata Bridge at 7 p.m., I heard the sound of waves hitting the shore. Usually, the other sounds in the neighborhood were loud enough to obscure the lapping of the water. It wasn’t romantic, though. The roar of thoughts in my mind was louder. “What will the situation be in Gaza if, God forbid, the pandemic spreads there?” I asked myself.

A health crisis and more

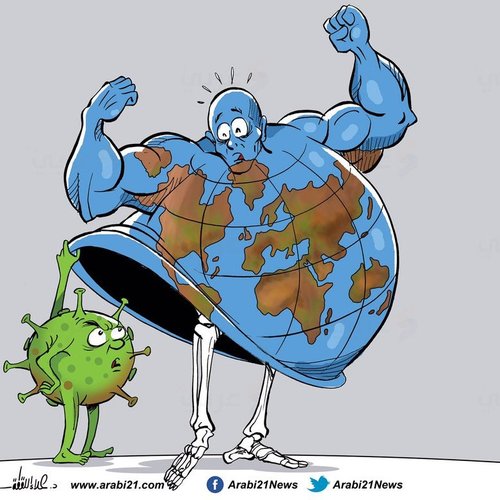

It’s now May 3, and the COVID-19 pandemic has become the defining health crisis of all time. Since its emergence in the Chinese city of Wuhan, the virus has spread to 212 countries, with almost 3.4 million confirmed cases and nearly 244,800 confirmed deaths. Turkey is no exception. To date, 124,375 infections have been recorded, along with 3,336 deaths. To slow down the numbers, the government has imposed strict procedures, closing public places (including mosques) and ordering curfew on the weekend. Staying at home has become an obligation.

I came to Istanbul in late 2018 to study for my master’s degree in international relations, thinking I could then use my experience in teaching Arabic as a tool of cultural diplomacy. Attending university, interacting with my professors and meeting other international classmates was a great benefit. However, the novel coronavirus arrived, spoiling this joy by forcing me to study from home, taking classes online. It reminds me of Israel’s blockade of Gaza, which spoiled my efforts to teach Arabic to students abroad through the Islamic University. Since its establishment in 2013, the university’s Arabic Language Center has been forced to conduct all of its courses online due to the blockade, which makes it nearly impossible for students to enter.

Everything else about the COVID-19 quarantine reminds me, in a way or another, of life in besieged Gaza. There are shortages of food and other goods in the markets, border crossings are closed, there is no way to fly, unemployment is high… the list is endless. However, if asked whether I’d prefer “doing time” in Turkey or Gaza, I’d without hesitation choose Gaza. At least there I’d be with my family and loved ones.

And that’s not just my opinion. “I wish Rafah Crossing wasn’t closed!” says my flat mate Hammam. He arrived in Istanbul from Gaza two months ago, driven by hopes and dreams of making a better life. But now, Hammam wishes he could be isolated with the 2 million people in Gaza, rather than with just three people (me and two other flat mates).

Our comparisons between Palestine and the current situation are nonstop. “Now I know how life in Israeli prison feels like,” says Diya, one of my other flat mates. “I bet Israeli prisons are much worse,” I thought to myself. We were sitting in the living room and our fourth flat mate, a Syrian named Ahmed, was in his room, which he rarely leaves as he studies for the university entrance exam. Hammam, who only occasionally sees Ahmed, mockingly replied, “Oh yeah, now we are sitting in the prison yard, and Ahmed is in solitary confinement!”

The irony of the Gaza blockade

On Sunday, March 22, the Gaza administration announced the arrival of the virus into Gaza, via two Gazans returning from Egypt. Luckily, the two men were immediately isolated in a school with other passengers. Four days later, five policemen who had been in direct contact with the men, also tested positive for COVID-19. Scary thoughts flooded my mind. Until then, I considered Gaza the safest place on earth, since it had been already largely sealed off from the world for a long time.

The spread of the virus into one of the most populated places on earth would be devastating. If the virus spreads past the crossing point into Gaza, it would spread like wildfire, due to the density of people and lack of working sewage and water treatment. The hospitals would be overwhelmed, and Gaza has few ventilators (estimates differ, but the most reliable one is 56) and 40 intensive care beds for a population of 2 million.

Thank goodness that to date, the Gaza government has swiftly tested all incoming travelers and quarantined for 21 days anyone found positive. None of the 17 who have tested positive have died.

Bad omens

When I was on Istanbul’s Galata bridge, I suddenly received a Facebook call. It was my family assuring me that Gaza was safe, and they were more worried about me. “Don’t go out,” my mother said, when she learned I was outside. I replied, “I am going to have dinner,” since restaurants weren’t yet shut down that time. “Cook at home. Eat anything, but don’t go out!” she insisted. “OK, don’t worry,” I agreed, and that was my last supper outside.

Napoleon once described Istanbul by saying, “If the earth were a single state, Istanbul would be its capital.” This makes me think of the future of the world after the pandemic. Bad omens had been showing up every day even before COVID-19.

Before the pandemic, populist and totalitarian leaders were ascendant in both the U.S. and Europe, signaling a hostile world for immigrants and other marginalized populations. Poverty in the midst of wealth due to a greedy, capitalist system threatened a deep economic crisis. COVID-19 has accelerated what seems like an impending doom.

It has exacerbated the rivalry between the U.S. and China, erupting into an exchange of accusations regarding who is most responsible for the spread of the virus. It has weakened the European Union. Borders have closed to desperate refugees and migrants. And the resulting economic crisis is being compared to the Great Depression.

When Gazans look at the world now, after the spread of the virus almost everywhere except there, and compare conditions to their own lockdown, economic crises and wars—which they have suffered for years—they can’t help but wonder if COVID-19 is really the Curse of Gaza, finally spreading to the rest of the world.