As Land Day (March 30) came to an end, with 16 demonstrators in Gaza killed in the first day of the nonviolent demonstration called the Great Return March, and the coming 70th anniversary of the Nakba (“catastrophe,” or when more than 750,000 Palestinians were forced from their homeland to make room for Israel), I am increasingly asked about origins of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. It is a pity that after 70 years of oppression of Palestinians, so many people still have no real knowledge about it.

I don’t know why there is such a void of understanding. The most clueless question I have heard is, “But why don’t you stop fighting, give up on your land and go to another place?” I am left speechless and shocked. At first, I tried to explain it this way: “What if someone came to your house, attacked your family and used force to kick you out?” Lately, though, I feel fed up and angry at this level of ignorance. It is exhausting to have to constantly explain and justify why I won’t give up the right to visit—much less live in—the land my grandparents and my relatives called home. The land of my roots defines my culture, my very identity.

Those who ask questions like this are usually white, self-centered and privileged to the point of taking everything for granted. They cannot begin to imagine the experience of Palestinians or any other colonized or oppressed people. They don’t even try to put themselves in our shoes and feel my grandparents’ pain when they were forced to flee their village of Beit Jirja and carry their three children to the Gaza Strip to find a new home.

They never asked, so they don’t know that the village became one of 530 “depopulated” Palestinian towns—ethnically cleansed so that Israel could exist as a Jewish state. Ever since, Palestinians have lived dispersed and stateless.

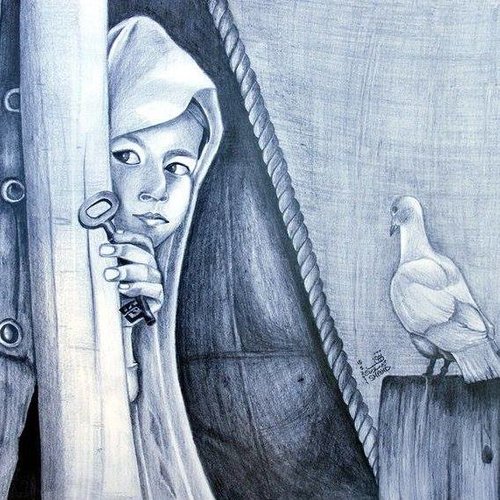

The first fact I learned about myself is that I am a refugee—a label I will wear all of my life. The first step I took was in the Gaza Strip’s biggest refugee camp, Jabalya. Camps are not only crowded places where hundreds of thousands of people live in cramped, old-fashioned houses and receive “humanitarian” aid from the United Nations. They are also vibrant hubs of humans who live, cry, love and laugh—while struggling nonstop just to survive. And survive they do, but they hold close to their hearts the memories of their original villages. The struggle makes us stronger, steadfast in our determination to return.

As a third-generation refugee, born and raised in the Gaza Strip but unable to go return due to the 11-year-old Israeli blockade, I now have another label—exile—like more than 6 million other Palestinians. My image of home is becoming increasingly surreal and imaginative. It is indeed hard to understand if you do not live it 24/7. Let me tell you what is hardest: It is being deprived of the freedom to choose. It is leaving Gaza to advance my studies and not being able to even visit.

The Palestinian lands of my heritage cannot be separated from the Palestinian struggle. My grandmother used to say repeatedly, “The Nakba is not only an event that happened and finished in the past. It is present and ongoing today.”

My request of those who have no clue about the Israeli-Palestinian “conflict”: Put yourself in my shoes. At least try. Would you willingly give up your right to return to wherever you call home?