There are 4,500 Palestinians in Israeli prisons; 220 are from Gaza. Visits are important for these detainees as well as for their families, but they are often denied by Israel for arbitrary reasons.

“Israel manipulates the conditions and rules of the visits as it wants without any control,” says Abdul Nasser Farwana, head of the Studies and Documentation Unit at the Detainees and Ex-Detainees Affairs Authority. “The visits’ requirements are strict and unfair. It permits many families to visit their sons once every month, some every two months, others every two or three years, and others are deprived for more than a decade.”

“The effects of depriving the detainees of visits are heartbreaking,” says the ex-detained Suleiman Al-Zari’l, who spent 19 years in prison. “The visits make the detainees overjoyed for weeks before and after seeing their families, which gives them great psychological comfort.”

A mother’s story

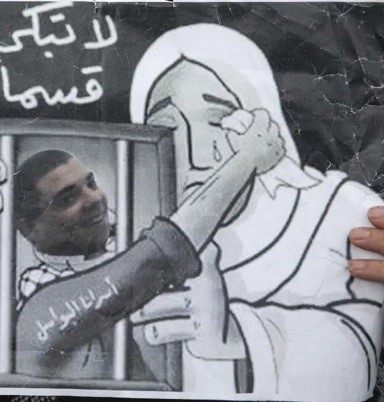

Ameera Al-Assar, 63, breaks down every time she sees her son Fares’ photo, which she keeps in her room. The picture shows Fares as a carefree and smiling young man. Now, 22 years later, Ameera cannot visit Fares in Nafha Prison in Israel because of Israeli restrictions on visits by detainees’ families.

“I would visit him once every two months before 2019. Since then, Israel has prevented me under fake security pretexts,” Ameera explains while holding Fares’ photo at her home in al Nussirat Camp in the middle of the Gaza Strip. “A 63-year-old woman with a curved back who barely walks threatening Israel? Can you imagine?”

In 1997, after finishing secondary school, Fares moved to the West Bank from the Gaza Strip in 1997 to work as an officer with the Palestinian Authority. At the height of the Second Intifada in 2002, he was driving a car in which six Palestinians who were part of the Fateh resistance shot dead six Israeli soldiers in Ayn Arik village in Ramallah.

After being pursued for five years, Fares was captured in Ramallah in March 2006 by special Israeli security forces and sentenced to 109 years in prison.

His family has sought to appeal the sentence.

“My husband Mohammed and I used to visit him together every two months,” Ameera said. “Then they denied me but allowed my husband. He visited his son five times in 2019; then all visits were suspended due to Covid-19.”

In 2020, when Ameera was 61 years old, Israel also prohibited her from accompanying her husband to Jerusalem, where he was to undergo heart surgery in Al-Makassed Hospital.

“They deliberately ruin our lives and do everything to upset us at every opportunity,” Ameera says, crying. “I haven’t seen Fares since 2019. I can’t wait to see him.”

During detainees’ family meetings at Nafha Prison, family members speak with each other for almost an hour through a handset phone. A glass wall separates them.

Every five years, Israel allows some families to hug their detained sons for a few minutes (at most) and take a photo, while indiscriminately preventing others this same experience.

“The last time Mohammed and I were permitted to hug Fares was in 2019 for 30 seconds. All families around the world hug their sons except us. I haven’t celebrated any Ramadan or Eid since his detention. I have made a promise we will never make or buy or eat Ka’ak El-Aid until Fares is free. May Allah help us and break the detention of all detainees.”

A wife’s story

Fatima Murtaja, 37, a mother of four, is in the same situation. She has not been able to visit her husband, Mohammed Murtaja, since he was detained while traveling to Turkey in 2017 for a business meeting. Mohammed was the Gaza director of the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency, TIKA,.

“It was the first time he traveled through Erezz Crossing,” Fatima says. “I still don’t know why he was detained. TIKA is a charity agency. They accused him of belonging to Hamas, but he denied that. However, he was sentenced to nine years. The ICRC [International Committee of the Red Cross], TIKA, and many human rights groups intervened but failed.”

Following that, Israel denied Fatima and her one-year-old daughter a visit with Mohammed. However, Mohammed’s mother and eight-year-old child, Farouq, were permitted to visit him in May 2017.

Fatima was denied again in August 2017, when Mohammed’s mother and ten-year-old child, Abdul Rahman, were allowed.

“When I was denied, my tears didn’t stop for long weeks,” Fatima recalls. “I still vividly remember the night before my mother-in-law and Farouq visited him. It was the hardest night of my life. I am his wife; why was I denied? What is the point? Why is his one-year-old denied? No one has the answer.”

After the sentence, Israel categorized Mohammed as a Hamas detainee, meaning he is deprived of visits and cannot receive clothes, money, or gifts from visitors.

“I tried many times to send him some clothes, but they refused to pass them on. I’ve never witnessed such brutality,” Fatima says.

The four children often argue with each other over who gets to sleep on their father’s pillow, as they believe his smell is still on it.

Abdul Rahman was 10 when he visited his father in 2017: “I stood on a chair in front of my father. There was a glass wall between us. I was scared to death — all I wanted was to hug him to feel safe. So, I begged for a soldier to let me hug my father for a few seconds, but he refused. I begged again and again, but the soldier didn’t budge.”

Fatima has reached out many times to the ICRC to allow Sara, now a toddler, to visit her father. Israel denied her requests.

“I still cry every Ramadan and Eid,” Fatima says. “Mohammed and my children used to go to the mosque together. Now the children go without him. Life is meaningless and unbearable without him. May Allah strengthen us.”

Asking for international pressure

In December 2021, West Bank and Jerusalem families had already resumed their visits following the two years of COVID restrictions. The Al-Mezan Center for Human Rights petitioned the Supreme Court of Israel to allow Gaza families to visit their detained relatives as well.

The court replied to Al-Mezan on Feb. 15, 2022, and permitted Gaza families to visit.

“The ICRC coordinated with the Israeli authorities to resume the visits,” explained Mervat Al Nahal, legal aid unit coordinator at Al-Mezan Center. “The first visit was on March 29, 2022, and two visits were made after that. Depriving any family of visiting its detainee violates the International Humanitarian Law and the Fourth Geneva Convention.”

Although the court said in its reply that only Hamas’ 70 detainees are prevented from receiving visitors, Al-Jihad’s detainees and others are still banned, according to Mohammed Alshiqaqi, the spokesman of the Muhjat Alquds association.

“All mothers can hug their sons except us,” Ameera says after wiping her tears. “I am sick of the Israeli occupation. I ask the international community to apply pressure on Israel to allow us to visit and see our sons in their prisons. I am tired of all this.”

Ameera does not believe the Israeli occupation understands the sentiments between detainees and their families. Like so many other Palestinians, she looks instead to foreign parties, waiting for signs of hope that she might one day see her son again.