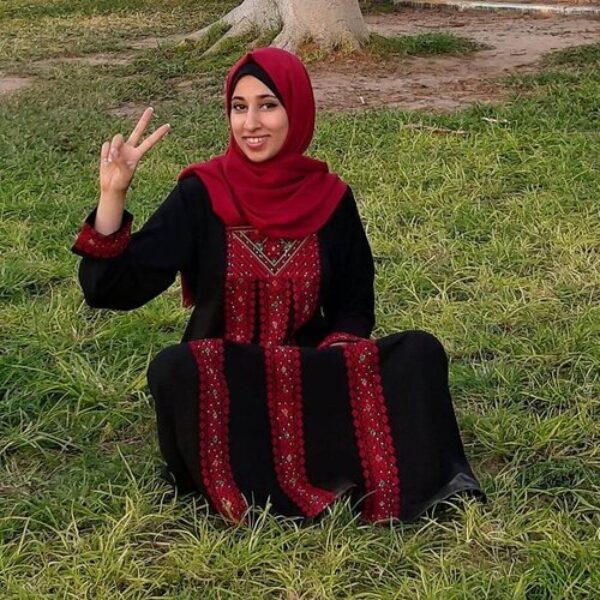

8 a.m. I start my day feeding my four kittens and their mommy Semsem. They are growing bigger and more energetic. My parents think I should gift them to people. But having a pet is a luxury in Gaza, with many barely able to provide food for their families these days. And meanwhile, other kittens are on their way. Yes, Semsem is pregnant for a second time!

I eat breakfast with my family and scroll through Facebook’s news feed on my phone for the latest updates on COVID-19. The number of active cases are rapidly escalating in Gaza. The Ministry of Health is warning that the current upward trend in infections could mean the pandemic will veer out of control here, like elsewhere. We must all stay home. The coronavirus is just another siege, a lockdown inside another, much-longer-running lockdown.

Since I have a smartphone, Mom asks me continuously for news about the virus. I find it ironic that we are finally stressed about something other than Israeli assaults! Many Gazans have begun to think that the pandemic has thrown the rest of the world into the same boat with us. At first, paradoxically, it seemed like Gaza was protected from the virus by the fortress that is the 14-year Israeli-imposed siege. That restriction on our movement has prevented most people from entering Gaza for years now. However, although the government took extraordinary measures to test and quarantine the few who were allowed to enter, we knew “community spread” was inevitable. And so it was.

Are we really seeking a shared humanity in illness and vulnerability? Is the coronavirus the great leveler? Is the world really the same as us now?

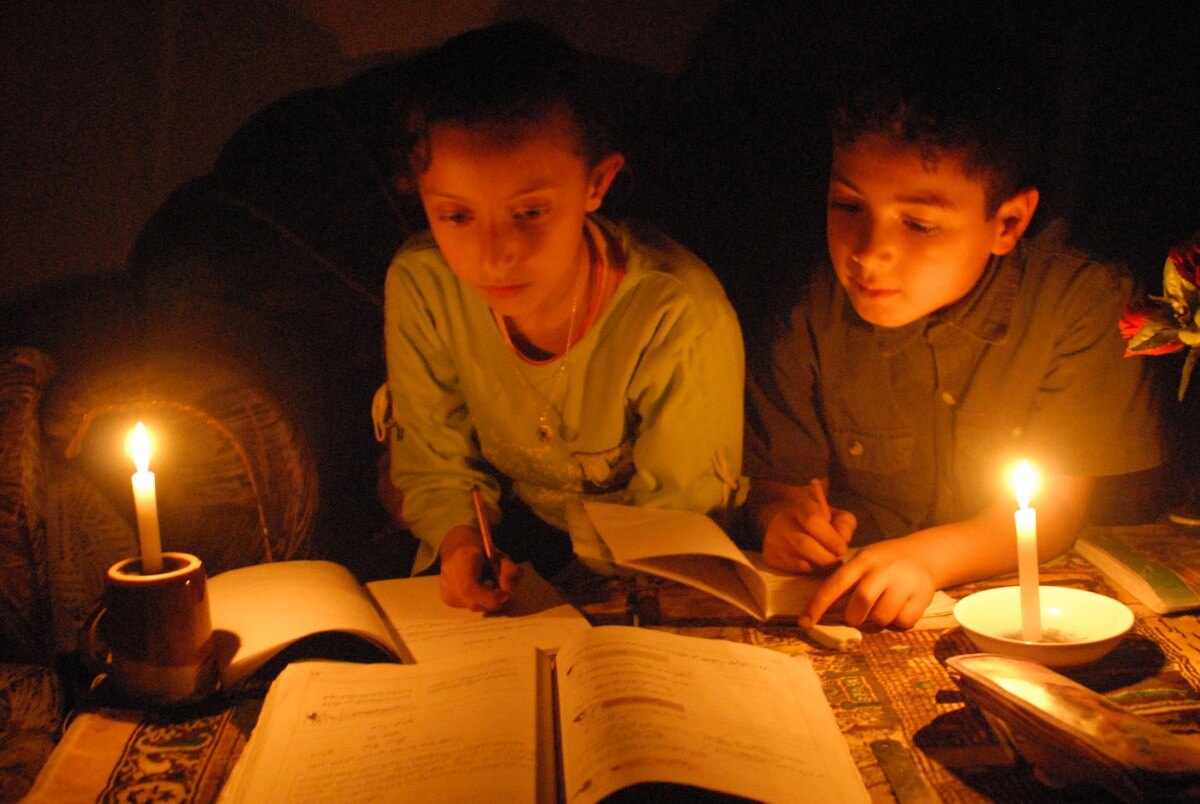

2 p.m. Everybody in my home is sweating. We are gloomy and fatigued. Our spirits are flagging. Our roof is a magnet for the sun’s heat, and the wind feels like an inferno outside our windows. It is the hottest month of the year. The weather broadcast says Palestine hasn’t had a season this hot for 118 years. Nobody can run our fans though because the only power plant in Gaza is shut down, as it does periodically. (In fact, I can’t recall when it was fully operational.) We change our clothes repeatedly, trying not to think of doing laundry. We all dream of having a shower, but our water tanks have been empty for three days. (In Gaza, most people store water in tanks on their roofs, using mirrors and the sun to warm it for bathing and dishes. The water is pumped from a spigot in the basement to the tanks when there is electricity.)

An hour later, my dad finally goes downstairs and carries buckets of water up. He toils up and down many times to get us sufficient water. We must, he says, use it only for necessary things like doing the dishes and using the bathroom.

4 p.m. We all head to the living room. We leave our bedrooms because they look right out over our neighbors inner area and they are talking loudly; we can hear every word. This is common in the Gaza ghetto, where 2 million souls are concentrated onto 345 square kilometers. Privacy barely exists. Everyone knows everyone else’s stories.

“Look! Employees are queuing in front of ATMs for their salaries. Aren’t they afraid of contracting the virus?” my sister asks.

“They have kids to feed. They need the money,” my brother responds. “What choice do they have?

“They are paid only 50% of their salaries anyway,” my sister sighs.

7 p.m. Piles of clothes need washing. We are running out of bread. There is supposed to be four hours of electricity every day, but we fall short. Uh, it’s extremely hot in here. Our bodies are on fire. We wave plastic plates like fans to create a puff of air. It will soon be dark. Oh, God, grant us patience. The young ones start complaining.

9 p.m. The children sleep on the floor to cool off. We turn on the LED lights, which are a safe alternative to the candles that too often cause fires. Houses have burnt down and whole families have died because of them. Mom asks me to call my brother Muhannad in Algeria to check on him. “My battery is almost dead; I’ll call him tomorrow,” I answer.

10:10 p.m. The electricity is ON! Everyone rushes to plug in appliances and charge phones. Mom turns on the washing machine and then hurries to the flour container and starts kneading dough for our bread. We help her with baking and later with packing the bread in bags. When all is done, I surf the internet. Breaking news reads, “Three siblings in al-Nuseirat camp die as a candle burns their home.” I gasp at Gaza’s fresh tragedy.

11:30 p.m. I rest my head on my pillow, thinking of my cat and her little babies, the horrible al-Nuseirat accident and my brother, who I long to call. That question jumps into my head again: “Can the suffering of the world be equated with ours?” My mind responds with an emphatic hell no!