My story begins neither on my birthday nor on my mother’s. It starts out the moment a seventeen year-old named Jamal (my grandpa, “Jeddo”) and his family left Bethlehem for Jordan in hopes of finding stability. At the time, job offers in Kuwait presented themselves to young ambitious minds in the region. This fueled Jamal’s desire to complete his high school degree, which was concluded with a series of difficult exams. He was so dedicated to studying that he rented a small room for that very purpose, away from the distractions of his younger siblings.

After successfully completing high school, he moved to Kuwait, where he assumed financial responsibility for his family. He joined the army, first as a translator, then climbing the ladder to much higher ranks. At one point a friend of his invited him to stay over in Beirut for a while. There he met Salwa (my grandma, “Teta”). They quickly became engaged and moved to Kuwait after marriage, where they lived for the next twenty years. Together they raised five children, the second of which was born in 1970. She is my mother, Lubna.

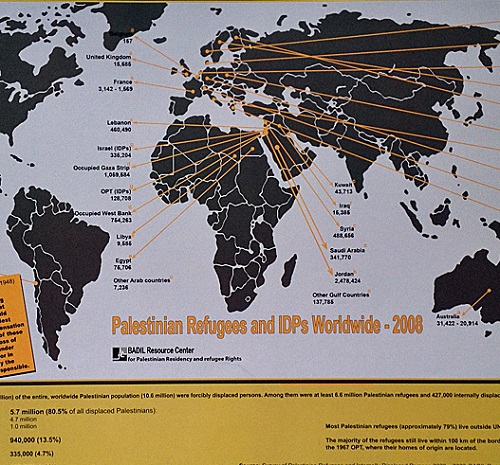

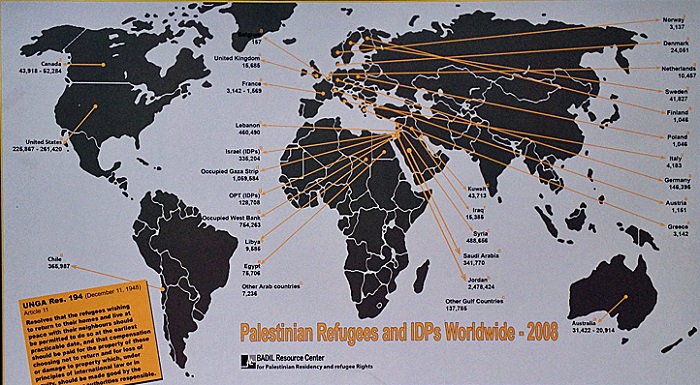

After building a complete life in Kuwait, Jeddo Jamal watched it all crumble in front of his eyes as the war in Kuwait unfolded. He and his family were forced to flee. Going back to Palestine was not an option due to the occupation and all of its complications. Eventually they wound up in Jordan, penniless, with all of their belongings back in Kuwait. As a result, they had to build up their lives yet again from zero. Seeking refuge twice over is not new to Palestinians. Many Palestinians have faced this not only in Kuwait, but also in Syria and other countries that have experienced war. Jeddo never psychologically recovered from the trauma of movement, loss and uncertainty. He never expressed his pain, but his eyes revealed more than enough.

Teta Salwa dealt with this trauma by resorting to religion; she found peace within it. Soon enough it became her obsession. She treated her children with an iron fist when it came to rules, despite previously being considered an open-minded and free-spirited person. Teta Salwa’s sudden flip in personality left Lubna desperate to attain her independence in order to work in her field of study as an engineer. She watched countless opportunities slip away from her as her mother stood in the way.

Another generation, more moves

In Jenin, Palestine, around the time my mother was born, Teta Samira home-delivered her second child, Saeed (my father). He grew up like any other Palestinian kid, with a childhood of adventure and trauma. The West Bank, including the village of Arabe in Jenin, had fallen under Israeli occupation in 1967. Being born under occupation affected every aspect of his daily life. By the age of ten, Saeed had already witnessed his best friend shot in the head in front of him on their way to school. At the age of fifteen, the consistent terror caused by the Israeli occupation caused his family to seek refuge in Saudi Arabia in hopes of a better life. They could not return to Palestine, so five years later they moved to Jordan, where Saeed dropped out of the university and started working in the tourism business.

In an unlikely coincidence, Lubna and Saeed met at a conference. My mother was ambitious beyond her time. She had a bachelor’s degree in engineering and a lot of work experience, allowing her to start the very first renewable energy company in Jordan. I wouldn’t say my parents fell in love, but they got along well and they associated the idea of marriage with stability. On the one hand, she attained independence from her parents, and on the other, he had a partner who offered to help him in business. The marriage was short-lived and brought anything but stability. I came into the story in 2002 on a Thursday afternoon. A few months before I was born, Israeli Defense Forces committed war crimes in Jenin. They killed at least 52 Palestinians and covered it up through a siege on the city, preventing any journalist or Human Rights organization from investigating. I was too young to comprehend it then, and never directly involved, but these events followed me silently, shaping who I am.

My dad was still registered as a refugee in Jordan, and so I inherited that status. My mom fought long battles to justify our existence in places where Palestinian refugees were not expected to be. For example, at the time, Jordanian law prevented Palestinian refugees from enrolling in non-UNRWA schools. She reached the Minister of Interior Affairs to get a permit granting me this privilege. This was neither the first battle nor was it the last; my mother fought so many legal battles to justify our status, our very existence as Palestinians in foreign land. Refugee status never defined me because my mom went above and beyond in paving the same opportunities for us as any other child. However, a sense of uncertainty followed me throughout my life wherever I was. The pieces of my identity were scattered, and I was too young to even grasp the factors that constituted it.

I found myself growing up in two homes, one with my mom and one with my grandparents. This was due to the divorce; my dad left for a job opportunity in Qatar, and when my mom travelled for short periods for work I stayed with her parents. However, in 2007, what was supposed to be a month-long trip was extended for a year and a half for reasons out of her control. At the time, my uncles and aunt were university students, and I grew very attached to them. They were my only source of happiness, always cheerful. Throughout that year I watched them leave one by one as each of them sought to belong somewhere and took opportunities to travel and build a life of their own. I remember begging my aunt not to leave for Germany, but soon I found myself alone with my grandparents.

At some point during the year and a half my mother was gone, my dad came back to Jordan. I moved in with him for six months, after which we travelled to Lebanon so that I could reunite with my mom. I spent the next eleven years with her and my brother in Lebanon, and it is where I continue to live today. None of my direct family members live here, so I have never felt so disconnected and alone. The last time we saw any of our direct family was five years ago, and it was only a short visit. I now have seven cousins, and I have only met two of them. My relatives are spread out around the world, spanning Turkey, Egypt, Germany, Jordan, Kazakhstan and Saudi Arabia, and those are only the directly related ones! Coming from a culture based on family bonds, nothing hurts more than being disconnected. We missed several family gatherings due to our financial inability to travel and complications regarding our residency status as Palestinians in Lebanon, which makes it problematic to leave the country.

Foreigners wherever we go

It’s rather difficult to maintain connections when each is struggling in a different country. Being a foreigner is never easy, and we are foreigners wherever we go. Other families have to come to an agreement on whose house should host the family gathering; we have to pick a country and figure out how we can all go there simultaneously.

Why couldn’t we all have just stayed in the same country? It’s because we don’t really belong anywhere. I was never born; I was thrust into unfolding chaos. I have always known I wasn’t truly from the place that bore me, nor have I ever felt as anything but an outsider the moment I stepped into the city I grew up in. A lot of the time, I feel like a small error in history. I don’t know what to answer when someone asks me “Where are you from?” Am I from Jordan? Lebanon? Palestine? or whichever country the future holds for me? One day I will leave Lebanon in search of stability, and I might not be able to return to Beirut, which I hold so dear to my heart, because living here for eleven years is not enough to grant me citizenship. No number of years will ever be enough.

I have heard people saying “Arabs have X states and the Zionists want only one Jewish state. how unfair!” I look back at all of the alienation I have suffered in Lebanon and Jordan simply for being Palestinian, and I struggle to find the words to explain that all Arabs are not the same, that “Arab” is an umbrella term that encompasses several ethnicities. Each country and group in the region is distinct with its own culture and long history. We are so much more than what the media portrays as Arab. Palestinians in diaspora are scattered, each individual desperate for stability, for settling somewhere, some when, but deep down, we know we are never truly home.